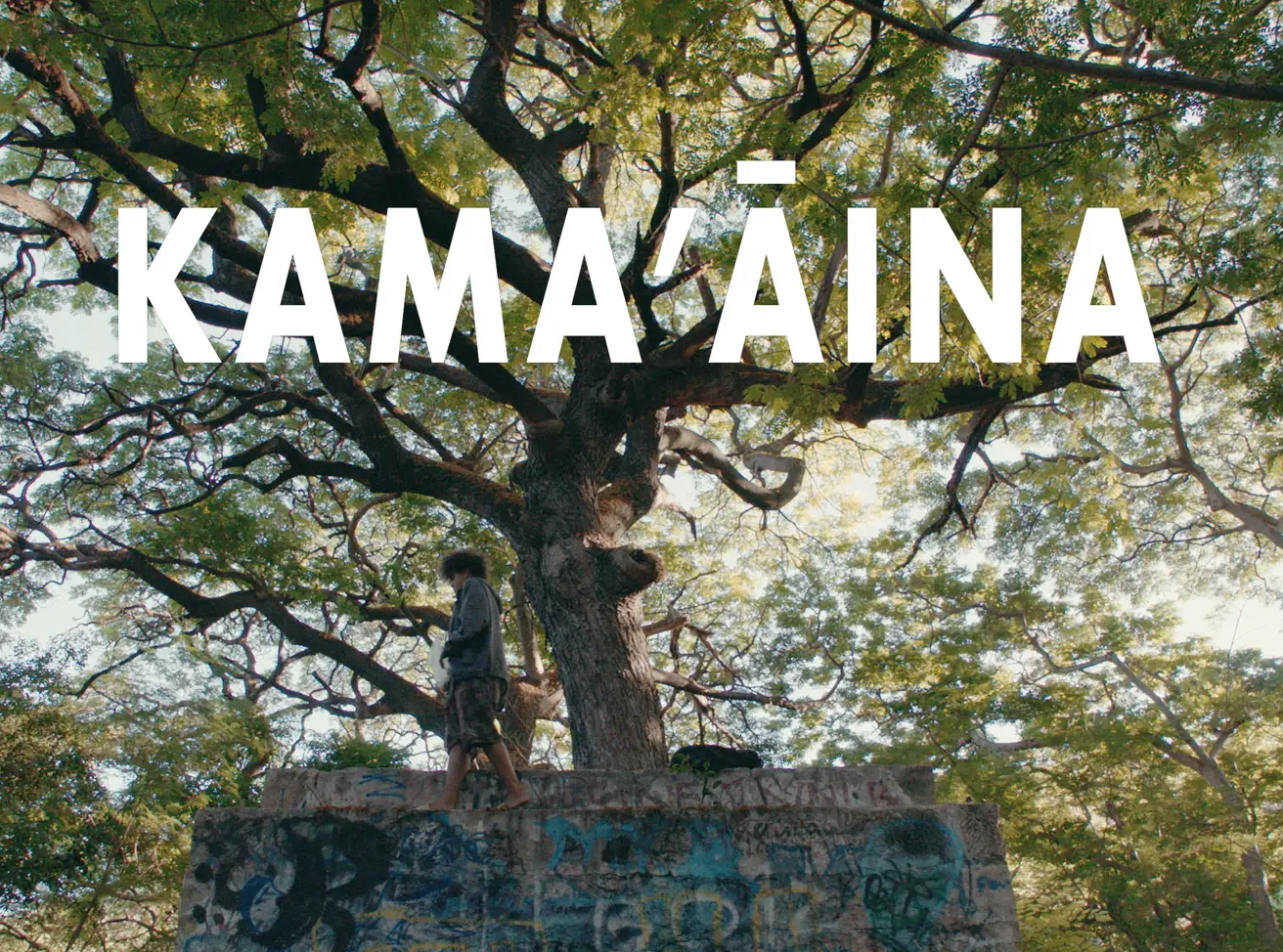

Kamaʻāina: Child of the Land (2020), a short film by Kimi Howl Lee, centers on the story of a gender-queer teenage character named Mahina played by Malia Kamalani Soon. Mahina lives on the streets of Waiʻanae, a rural, mostly Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) and Pacific Islander community on the island of Oʻahu. Throughout this document, I will refer to Mahina with the pronouns “we/us/our” interchangeably as a way of decolonizing a gender queer identity. As an Indigenous gender queer character, “they/them” and “she/her” just felt a little too White and Western for a cultural personality like Mahina’s. Also, I wanted to honor the collective and communal ways in which we, as Kānaka Maoli, embody our identity. Struggling with our body, its menstrual pangs, and the precarious housing conditions that animate a quest for something better, Mahina strives to overcome the odds against us in radical ways. The film asks: How do we navigate Queer Indigeneity in a settler state while creatively accessing care for ourselves and others? How do we as modern Indigenous queer and trans Pacific Islanders survive when our environments are hostile to our existence? And finally, what is a puʻuhonua and how do we become one?

The Fallout

At the beginning of the film, Mahina walks anxiously along the rooftop of an abandoned concrete fallout shelter, a remnant of WWII. The prominence of the structure leads us to ponder the conditions that gave rise to its creation and the people for whom it does and does not belong. Colorful graffiti and overgrowth cover the fallout shelter. We see how nature and people resist war and destruction through the radical forces of perseverance and creative indignation. Mahina’s character is a metaphor for Kānaka Maoli (Hawaiian people), our resistance to the settler colony and our ability to bounce back after chaotic disruptions, historical failures and apocalyptic setbacks.

Like Mahina, Kānaka Maoli who refuse to disappear struggle to survive and thrive in a settler state. It is this hardship that links Mahina’s literal fallout to the historical and institutional exploitation of our lands and people. Eating through the last of a food stash, Mahina confronts these historical conditions as they are woven into the fabric of our story. In this story, a broken hearted, queer, Indigenous teenager seeks an “elsewhere” of social belonging in a world that attempts to dispose of us. There is this assumption in the settler imaginary that all youth are straight and virginal and that all families are functional and heteronormative. This leads to political alienation and social ostracizing that leave our kids like Mahina without support and out on the streets. However, in the film, as in life, we are reminded that many of us, like Mahina, who come from broken homes, are unwilling to disappear and continue to persevere in our movements for change.

As a māhūwahine (Native Hawaiian transgender queer woman) who has had to confront many of the struggles faced by the character, Mahina, in my own life, I seek to affirm the “fallout” that re-imagines ea (breath, life, sovereignty) beyond the settler colony. A settler colony does not allow Indigenous people to embody the power of our queer stories. In this film, however, we are encouraged to take that leap, as Mahina does, to find ourselves without apology and shame. We are endeared to Mahina precisely because the struggles we face are systemic ones that cannot be individuated. Being without shelter, without food, and without a maxi pad for menstruation is literally a series of unfortunate events that are beyond Mahina’s fault. It is precisely these misfortunes, however, that allow us to understand Mahina’s desire for movement and puʻuhonua as a matter of environmental and social justice. Puʻuhonua serve as a place of refuge and rebirth. They also affirm the sacredness of life in a time of war and emphasize the values of love and community—interdependence, as well as a connection to self and to ‘ohana (extended family and support network).

The Restaurant and the Store

Finding respite on a table in front of a local restaurant known as Barbeque Kai, Mahina confronts a cashier who demands payment for being on the premises. For some viewers, the cashier is “just doing her job.” Afterall, it is a reasonable idea to expect that those who sit on the premises of a restaurant are paying customers. However, such a reasonable expectation must be understood within the political context of the settler colony that devalues Indigenous, queer, and underserved individuals. In this context, to have a seat at the table one must have money and the right appearance. We must render ourselves legible to capitalism. Unable to afford menu items somehow invites cruelty and punishment. Mahina is embarrassed and shamed by the cashier who happens to be a woman of color. However, in refusing to accept this shaming, Mahina leans into our creative indignation to find common ground. As a result, the cashier, however begrudgingly, responds to Mahina’s request for ice water, perhaps knowing that the struggle is all too real.

Regardless of the unpleasantry of the exchange, scoring a cup of ice water and a perfectly edible half-eaten meal of chicken katsu from the rubbish can is a win for Mahina. One’s refusal to accept shaming is almost always divinely rewarded. Following the restaurant scene, Mahina “commandeers” two candy bars from a nearby convenience store by stuffing them into a blue slushy. We feel a sense of delight by this act of rebellion. These stores are overstocked with goods yet there are always one or two uncles sitting out in front with open hands who would be happy to have just one cigarette, one quarter, or one soda. These stores are everywhere but no one in our neighborhood knows the owner. These franchise stores are able to sell us sugary delights because we as a people are often too bitter from historical injustices and traumas to sufficiently resist the sweetness. Thus, in a way, Mahina’s “commandeering” practices respond to systemic failure that are literally built on the disenfranchisement and ill health of our people who continue to face criminalization for being Indigenous, queer, and poor.

The Park

Exhausted, Mahina takes a nap at a public park known as Kalanianaʻole Beach Park. The park has two beaches on either side of it. Connected by a long stretch of sand, the scene harmonizes with the sounds of laughter, music, and noise as families, children, parents, and grandparents intimate the space to co-create a place of refuge. However, the refuge quickly turns into a nightmare. As Mahina naps, the cellular phone, the only means of support we have, is stolen. Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon experience for the unsheltered. However, the loss is significant. For millennial cyborgs and digital Natives like Mahina’s character, the cell phone is especially important, representing “life” itself and so to lose it—just as one is waiting for a lover to return a phone call—is almost unbearable. Adding to this loss, Mahina encounters a friendly but ignorant American social worker who offers toothpaste and maxi pads. However, as if these hygiene products served as bait, the social worker also offers to call in the police to help, sending Mahina into a state of panic. Social workers should know that sometimes “home” is not a safe place and that for many queer youth it can be hell on earth. Abuse, neglect, and condemnation are too often a part of our everyday life. Sometimes “elsewhere” is the only place we feel safe. Moreover, in a world where our very existence as unsheltered Indigenous, queer youth is criminalized, the last people on earth we would want to see or talk to is the police. In police custody, a runaway youth is institutionalized in juvenile detention and then returned home even when it is unsafe.

Compassionate Disruption and Puʻuhonua

In 2014, Mayor of Honolulu, Kirk Caldwell, began to implement an aggressive program to clear chronic “homeless” people from public parks and sidewalks to make room for upscale housing and tourist projects. He called his strategy “Compassionate Disruption.” Emphasizing the criminalization and disruption of Indigenous bodies and lives in public spaces, these settler laws created a spectacle of land evictions, revealing an obvious paradox—the perpetuation of harm (not compassion) towards homeless/houseless and “home-free” folks and the chosen family arrangements and Indigenous systems that sustain us. I introduced the concept of “home-free” in a past article entitled, Home-Free and Nothing Less, to get away from reducing anyone to a less-than-human sign or symbol.

However, here I want to set the context of “Compassionate Disruption” as a form of state violence that moves from making life difficult to unbearable for people who are too naive, poor, and oppressed to adequately defend themselves. “Compassionate Disruption” betrays the best interests of the public. Instead, it attempts to bankroll land developers with public funding by disavowing the root problems of homelessness, morbidity, and poverty. Rather than fixing the dilapidated schools and building houses for the poor in our neighborhoods, city and state officials are always thinking about the next grand housing or hotel project for the rich.

Puʻuhonua O Waiʻanae (POW), in contrast, embarked on its own unique plan by defending the right of all people to exist in public spaces. Under the direction of POW leader, Twinkle Borge, the village helped to transform the perception of and stigma attached to tent city encampments and its people by creating community-first alternatives regarding the way people talk and think about homelessness. In Kamaʻāina, Mahina makes her way to Puʻuhonua O Waiʻanae, the largest home-free village in contemporary Hawaiʻi in the final scene of the film. Here, we are introduced to Twinkle Borge and members of her ‘ohana, one of them being my former mentee, Nainoa Brown Kahananui, who plays the role of Mahina’s high school classmate. The meeting between Mahina and Twinkle is a subtle one, but we get the sense that for Mahina’s character the connection is life changing. Twinkle shows Mahina around the village, illuminating a safe place to sleep, clear pathways, healing garden spaces, and ocean views. Unlike the scene where Mahina is confronted by a social worker unfamiliar with local Hawaiian culture and etiquette, Twinkle listens to Mahina and does not impose herself. Instead, she provides Mahina with a space to create and recreate “our” own destiny, giving “us” a sense of safety. In the end, Mahina has finally found the “elsewhere” we’ve been hoping for, an “elsewhere” that feels like a real home, a place where we might want to return.

Translated from Hawaiian to English, the term “puʻuhonua” means “earth barrier” and it also means “refuge.” As a refuge, puʻuhonua can be a person, a place, or a thing. Its main function is to create space for inclusion, harmony, protection, and safety. By valuing ‘āina (land/all that nourishes), puʻuhonua contradict the concept of property under the conditions of a settler state that erases and replaces Indigenous and Immigrant cultures, peoples, and values with those of the dominant settler society. Puʻuhonua thus resists the brutality of this imposition. By contesting the settler state in ways that evade captivity, punishment, and shame, puʻuhonua provide rigorous forms of accountability and access to resources without failing connections to community, humanity, self-care, and preservation. It is in this spirit of puʻuhonua then that we find solace at POW, a place “elsewhere,” a place between the forest and the sea where we return to the source of our ea, our relations to everyone and everything, and our ability to bounce back—to heal beyond the settler colony.

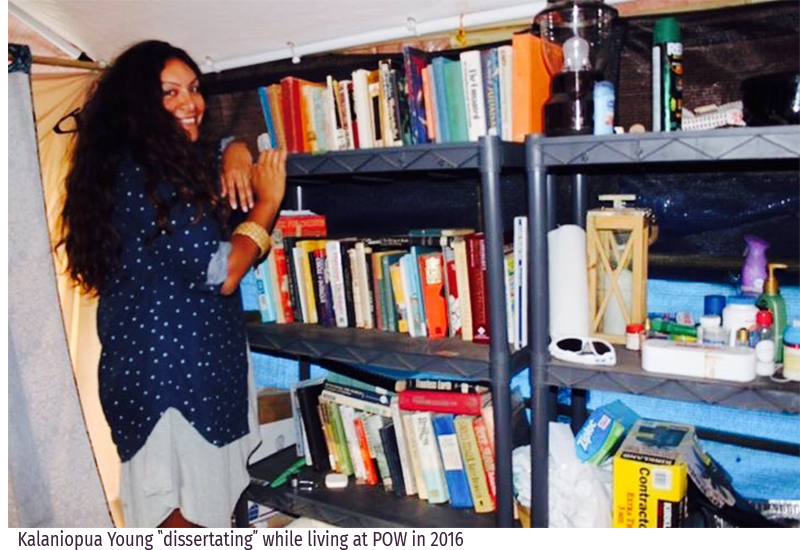

Kalaniopua Young is a māhūwahine+ and QTPI (Queer/Trans Pacific Islander). She is a recent PhD from the University of Washington’s Department of Anthropology. A former board member of the United Territories of Pacific Islanders Alliance (a Faʻafafine led organization in Seattle) and a founding member of Tent City Kweenz at Puʻuhonua O Waiʻanae, the largest home-free village in contemporary Hawaiʻi. Today, she is a lecturer at the University of Hawaiʻi and Board member of KAHEA: The Hawaiian-Environmental Alliance.

You can find further reading and watching in links throughout Kalaniopua Young’s essay and the resources listed below.

— “Hawaiian Style Graffiti and the Questions of Sovereignty, Law, Property, and Ecology” by Masahide Kato can be found in AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples

—Then There Were None—a documentary by Elizabeth Kapu‘uwailani Lindsey

— “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native” by Patrick Wolfe can be found in the Journal of Genocide Research

On August 10, 2020, join Kalaniopua Young, filmmaker Kimi Howl Lee, lead actor Malia Kamalani Soon, and Pu’uhonua O Wai’anae community leader Twinkle Borge for a special community discussion on the film Kamaʻāina, and the important societal issues it raises. Mahalo to the Honolulu Rainbow Film Festival for partnering with us to make this happen. For more about this event, CLICK HERE.

Leading up to this important discussion, we will be hosting a Try Think online watch party on August 5, 2020. Come and join us to reflect and share your own thoughts about the film. For more about this event, CLICK HERE.

All photographs, with the exception of the first photo (a screen capture of the film), are courtesy of the author.

Nā Mana Wai aims to highlight a diversity of community voices from around our islands and is intended to raise important questions that will lead to continued productive discussion. The opinions expressed here do not represent those of Hawaiʻi Council for the Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.