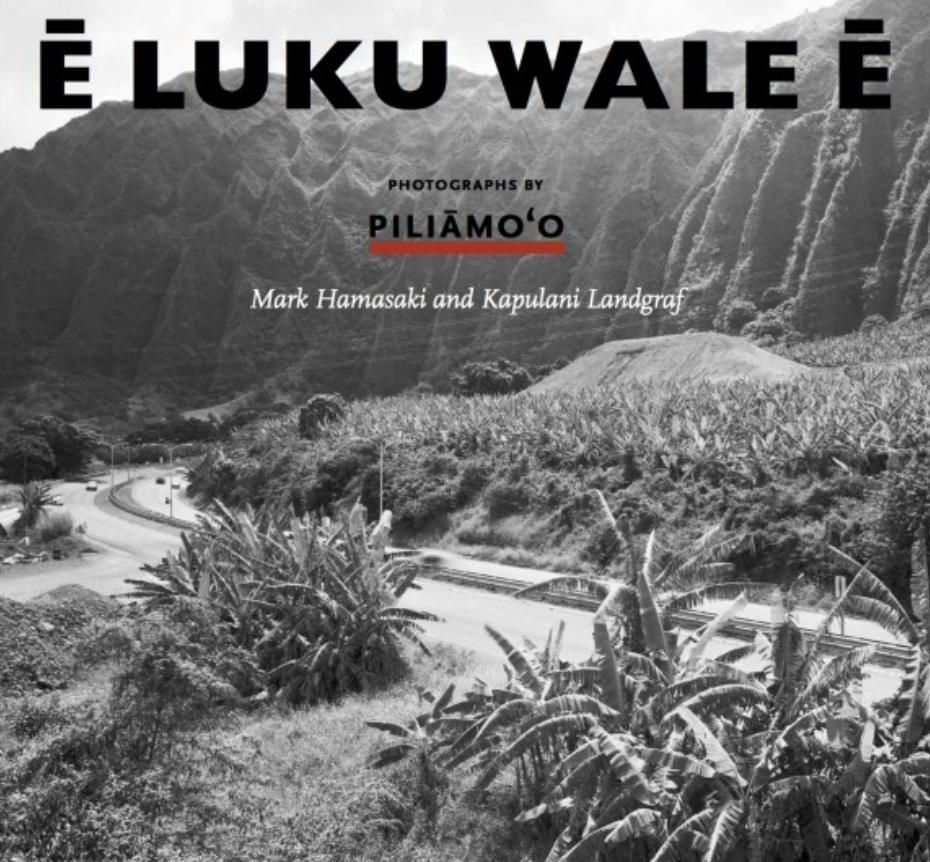

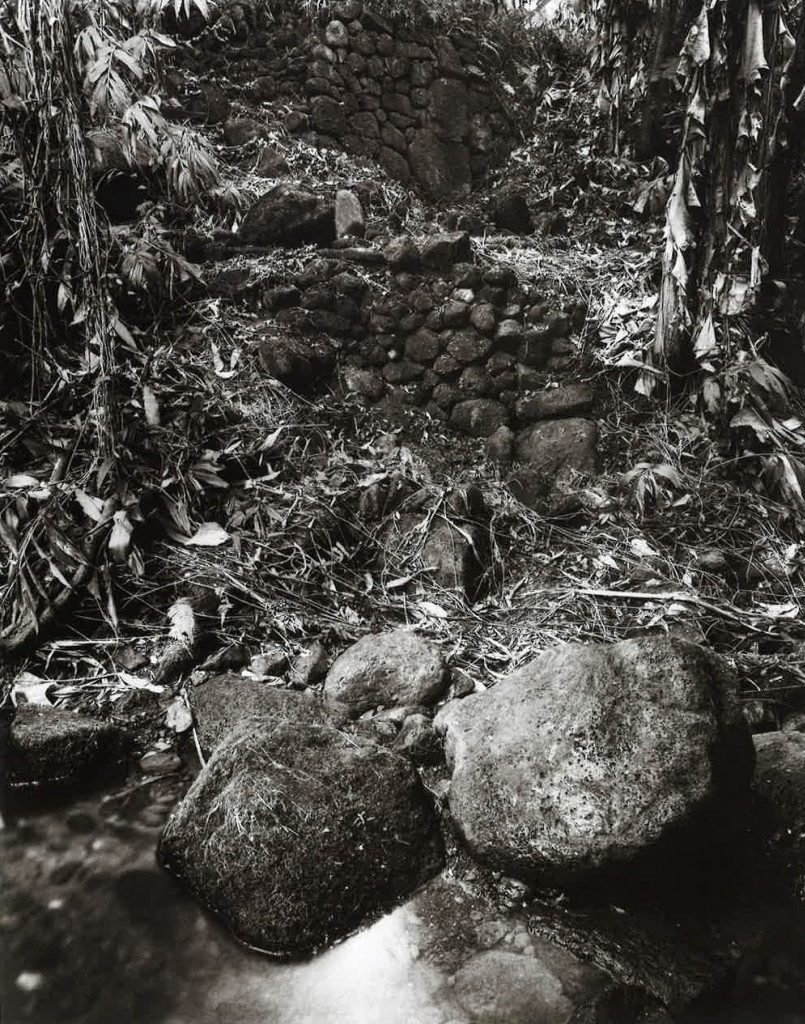

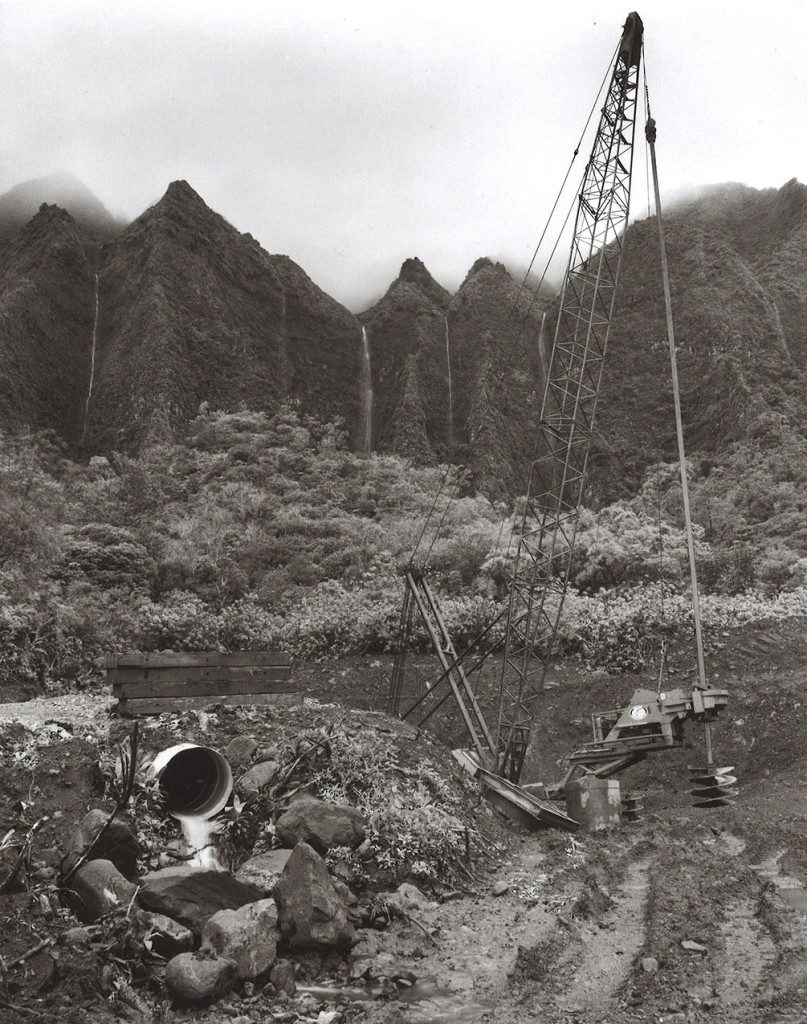

Ē Luku Wale Ē: Devastation Upon Devastation, by Piliāmo‘o, a collaborative name for photographers Mark Hamasaki and Kapulani Landgraf, visually documents sacred sites, as they were and as they are erased; to tell the history of a massive engineering project that created the H-3 freeway–a route that traverses people and cars from Hālawa Valley through the Ko‘olau range, emerging above Ha‘ikū Valley, winding its way down into Kāne‘ohe; and to visually and verbally lament the loss of what was and what had deep meaning to Native Hawaiians.

Ē Luku Wale Ē: Public Programs

Starting in February of 2016, Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities, in partnership with community groups, presented a series of TALK programs focusing on Ē Luku Wale Ē: Devastation Upon Devastation by Piliāmo‘o, a collaborative name for photographers Mark Hamasaki and Kapulani Landgraf.

These hosted programs were designed to bring the local community together with humanities perspectives to discuss and think about Hawai‘i’s recent history regarding large-scale public projects and the use of sacred lands and places and the people who claim them. The aim of TALK was to engage multiple viewpoints by bringing awareness and raising questions to generate more knowledge about the Hawai‘i Interstate H-3 project, which remains as one of the most contested projects in Hawai‘i and serves as a timely reminder of current ones.

The opportunity to discuss these issues will help to understand and uncover what was literally covered over, or displaced, and finally dismantled, to complete the Hawai‘i Interstate H-3 Highway, formally known as the John A. Burns Freeway.

Ē Luku Wale Ē serves several significant functions: to photo-document sacred sites, as they were and as they are erased; to tell the history of a massive engineering project that created the H-3 freeway–a route that traverses people and cars from Hālawa Valley through the Ko‘olau range, emerging above Ha‘ikū Valley, winding its way down into Kāne‘ohe; and to visually and verbally lament the loss of what was and what had deep meaning to Native Hawaiians

Ē Luku Wale Ē: Authors’ Discussion and Q&A

For the first TALK program, the following photographers and contributors who worked on Ē Luke Wale Ē shared their experiences and expanded upon their research and contributions. Vocal artist Aaron Salā gave voice to the kanikau.

Mark Hamasaki, photographer

Mark has taught photography at Windward Community College since 1984. He is currently the photography professor at Windward Community College and is the Humanities Department Chairman. Together with Libby Young, retired Windward Community College journalism and English professor, Mark was named among The 10 Who Made a Difference in Hawai‘i. They were cited for their efforts to secure $12.5 million for Windward Community College’s Master Plan. He has exhibited and published his photographs and collaborative works locally, nationally and internationally. Mark lives in Ha‘ikū, O‘ahu.

Kapulani received the 2013 Visual Arts Fellowship from the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, and the 2014 Joan Mitchell Painters & Sculptors Grant. Landgraf’s books, Nā Wahi Pana o Ko‘olau Poko(University of Hawai‘i Press, 1994) and Nā Wahi Kapu o Maui (‘Ai Pohaku Press, 2003), received Ka Palapala Po‘okela Awards for Excellence in Illustrative Books in 1995 and 2004, respectively. She is an assistant professor of Hawaiian Visual Art and Photography at Kapiʻolani Community College, Kalāhū, Hawaiʻi.

Barbara Pope, book designer

Designing and producing illustrated books in Hawai‘i for over thirty years, Barbara is Principal of Barbara Pope Book Design and a founding partner of ‘Ai Pōhaku Press. Her expertise is in graphic design and publishing. ‘Ai Pōhaku Press specializes in high-quality books about the natural systems and cultural traditions of Hawai‘i and the Pacific.

Dennis Kawaharada, author of “Introduction”

Dennis is an English professor at Kapi‘olani Community College and a publisher of the literature of Hawai‘i, Asia and the Pacific.

Richard Hamasaki, author of “Preface” and English translation poetry editor of the kanikau

With a teaching career in Hawaiʻi that spanned 40 years (1975-2015), Richard spends time with family and continues to work independently and collaboratively on do-it-yourself projects related to the arts in Oceania.

Aaron Salā, vocal artist

Aaron has performed in such international venues as Carnegie Hall (New York), Wembley Arena (London), the Wilten Basilica (Innsbruck, Austria), Bunkamura Hall (Tokyo) and Hawai‘i Theatre (Honolulu). Aaron began studying the art of Hawaiian chant with Kalani Akana five years ago in preparation for his studies to achieve the rank of ho‘opa‘a under Akana’s tutelage, the ‘uniki for which he underwent in 2014. He is the 2006 recipient of the Hōkū Hanohano Award for Most Promising Artist. Aaron will chant the kanikau, Ē Luku Wale Ē.

Ē Luku Wale Ē and the Lessons of H-3: Learning from the Past and Caring for Our Futures

Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities and Windward Community College presented a second TALK program that continued to look at the book Ē Luku Wale Ē: Devastation Upon Devastation to bring forth dialogue that explores recent history featuring one of the original archaeologists who worked on field research and excavations of the vast agricultural system and the Kukuiokāne heiau beneath Keahiakahoe. This discussion program explored where we are today in the field of cultural archaeology, and what is being done to take care and nurture public place and space.

Scott Williams shared his perspective on what happened before construction on the H-3 freeway began in the 1990s and talk about his role and fieldwork findings while working as the Bishop Museum’s senior staff archaeologist on the Ha‘ikū Valley side of what was to be the H-3 freeway structure. Scott currently resides in Washington state and is the cultural resources program manager of the Washington State Department of Transportation.

Kapulani Landgraf talked about her research in the field and at repositories, where artifacts and field notes from the H-3 project are contained, and how she used those resources to inform the book Ē Luku Wale Ē as well as how the project has continued to resonate in her work as an artist. Kapulani is an assistant professor of Hawaiian visual art and photography at Kapiʻolani Community College.

Kekuewa Kikiloi presented where archaeology is today after the construction of the H-3 freeway. Kekuewa represents a new generation of archaeologists who take into account indigenous knowledge, resource management and cultural revitalization while researching and studying human activity. He is an assistant professor at the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Hi‘ilei Kawelo, executive director of PaePae o He‘eia, represented the community and the rebuilding of Kāne‘ohe’s Hawaiian culture, specifically in the Ha‘ikū Valley and He‘eia region. Her perspective of caring for the land broadened the discussion and showed that what happened in the past could inspire us to continue to care for our Hawai‘i today.