This is a letter of aloha and kanikau for my kupuna kualua, Keohokalole and my kupuna kuakahi, Annie Keoho and all of my kūpuna whose lives were forever changed by the maʻi ho‘oka‘awale ‘ohana.

Sometime before 1879, Keohokalole contracted Hansen’s disease and was sent to live in Kalaupapa with her kōkua, David Poʻai. I do not know where Keohokalole was originally from, but David was from Hamakuapoko, Maui where they lived together. David was allowed to stay with Keohokalole all the remaining days of her life. I take solace in knowing that she did not live or die alone in Kalaupapa. But all of their children born in Kalaupapa, were taken away from them and sent to live as orphans in Oʻahu. Sadly, this is all we know of Keohokalole. My aunties have returned to Kalaupapa several times to find some trace of her, but it seems she was buried among the many unmarked graves. I search for her in the Papakilo Database and the nupepa and I turn to scholars like Noelani Arista and her work on kanikau, to map the winds and rains that she would have known. Keohokalole would have been among those who greeted Queen Liliʻuokalani when she came to visit in 1881 but beyond the stitching together of a few fragments of moʻolelo, I cannot know what life was like for her or how it felt as her children were taken from her arms, knowing she would never see them again. Keohokalole, e lei no au i ko aloha. I find myself thinking about what it means to be born in the time of a pandemic into a world were those who are ill cannot touch those they love. What does that mean for parents and what does that mean for their children?

Annie Keoho was born in Kalaupapa in the middle of such a time and at a very young age, maybe seven or eight years old, she was separated by law from her ʻohana, and sent to the Kapiʻolani Home for Girls in Kakaʻako. She was housed in a two-story building on the waterfront, surrounded by a rapidly changing Honolulu, cared for by nuns from the Order of St. Francis. I often wonder if she stared across the sea longing to return or if she cried herself to sleep. What did the world become for her?

We know Annie Keoho trained as a nurse and moved to Maui, soon after the overthrow of the Kingdom in the mid-1890ʻs to work at Malulani Hospital in Wailuku. While working there, she met a young plantation worker named Ichisaburo Nakata who had arrived on Maui around 1886. Ichisaburo was from a farming family in Yamaguchi-ken prefecture, Japan. During a severe economic depression, Ichisaburo went to the docks to join the laborers coming to Hawaiʻi. A man named Masaji Enomoto did not respond when his name was called, so Ichisaburo raised his hand and assumed Masaji’s name. This is how I, and my father before me, became Enomoto, rather than Nakata.

Ichisaburo Nakata became known as Ichisaburo Nakata Masaji Enomoto in Hawaiʻi. He gave up his name, left his family to work the sugar plantations of Hawaiʻi to survive. While working in the fields, he injured his arm and Annie Keoho became his nurse. I have always loved that their relationship grew out of a moment of healing, during a time of great turbulence and loss. I wonder what was their language of aloha? Did she learn Japanese and he Hawaiian? They lived together in Haʻikū and had six children together. Annie Keoho continued to speak ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi to her keiki everyday, even though it had become forbidden, and in an act of claiming his own family’s lineage, Ichisaburo initially registered his childrenʻs births under the name Nakata, rather than his assumed name of Enomoto. These small but necessary gestures of holding on to to their genealogies are what I carry with me in in these uncertain times.

It comforts me to know that Annie Keoho was able to reunite with her father, David Poʻai, as an adult, and would take trips to visit him and his new wife ʻOpupale in Hoʻolehua, Molokaʻi. It was during one of these visits with her father that she gave birth to my kupuna kāne, Toshi Enomoto, in 1906, but the tragedy of illness continued to haunt our ‘ohana. In 1914, Ichisaburo contracted tuberculosis. His attempt to recover at Kula Santorium proved unsuccessful so they brought him home where he died with his keiki around him on March 13th.

The following year, on February 7, 1915, the day after his seventh birthday, Annie and Ichisaburoʻs youngest son Rudolph Stephen Takasuke Enomoto joined his father, it is said from a broken heart. He simply could not bear the loss of his father. How did Annie Keoho hold the world together for her remaining keiki in the days that followed? How did she awake each morning? How did she not simply give up?

My father, Stephen Noel Ichisaburo Enomoto carries the name of these kūpuna and I have found that many of my relatives are named in much the same way. They carry these names so they may live. From the moment we have had to shelter in place, these moʻolelo have filled my head and only now am I beginning to understand the depth of mourning and the magnitude of resistance that all of my kūpuna had to hold. These moʻolelo have become part of my everyday as I think about the ocean’s distance between myself and my parents and my sister, as we live through this new pandemic. I do not know who I would become if they were suddenly taken from me.

As I sit in these moʻolelo of the past and present, art, in all its forms, has become the space I turn to when the world makes no sense. One artist I look to is my friend and Bay Area based painter, Cece Carpio, who makes visually stunning images of her indigenous ancestors and other indigenous peoples in the Philippines. Her work says we, the indigenous, are still here despite colonial and state attempts of erasure. Artists and educators in this time of distance should be asking ourselves, what marks do we need to make, what do we need to build to connect us to our kūpuna and to our ʻāina?

When I think of connecting to my kūpuna and our ʻāina today, it is by doing everything I can to protect it from continued environmental and human devastation. COVID-19 has given most of us a time to pause and to question the deadly impacts of unchecked development and never-ending wars. But as I write this letter, the U.S. Navy recently announced the 27th Rim of the Pacific Exercises (RIMPAC), which is the largest group of naval exercises in the world and has occured every two years since 1971. In 2018, RIMPAC involved 25 countries, 51 ships, 200 aircraft, and 25,000 military personnel. All of which came onto Hawaiʻi shores conducting live fire training on the sacred lands on Pōhakuloa, amphibious assaults on our beaches, and missile launches into the ocean. Through the usage of low frequency sonar, RIMPAC devastates marine life, potentially causing injury, permenant hearing damage, and fatal events such as whale strandings on Hawaiian beaches. This injury and loss of life is called “incidental takes.” There is nothing incidental about this kind of environmental damage and loss of life.

Some of the highest and fastest growing rates of COVID-19 have been among the military, especially the Navy, and rather than cancel RIMPAC to give its personnel time to heal, the Navy insists on conducting a two-week “at sea-only” version of RIMPAC that will include “anti-submarine warfare, maritime intercept operations, and live-fire training events”.

At a time when the United Nations is calling for a global cease fire, RIMPAC partner governments want to play at war and not only risk the lives of their military personnel, but our lives and all marine life. These are completely unnecessary acts that center violence and capital over life. How can we collectively plant seeds to create and nurture genuine security and grow roots in aloha ‘āina futures?

As I observe these unnecessary gestures by the state, I think of the artist Doris Salcedo. In an interview on Art21, she discussed her work, Unland that required drilling hundreds of tiny holes to sew hair into the wood. It was extremely labor intensive and Saldeco acknowledged that to do this was an absurb gesture. Unland was made during the time known as “La Violencia” in Colombia when the paramilitary was massacring hundreds of people. The gesture of sewing hair through wood was a recognition of the fragility of life and it seemed less absurd than the deaths surrounding her. During these days when everything sounds like noise, the brevity of poet nayyirah waheed combines everything I am feeling with these lines from Salt, “all that was/ taken/ from me. is still here” —roots| immortal (154), and so I remind myself and my ancestors, we are still here. Our moʻolelo are still here and in remembering, we are all made stronger.

me ke aloha,

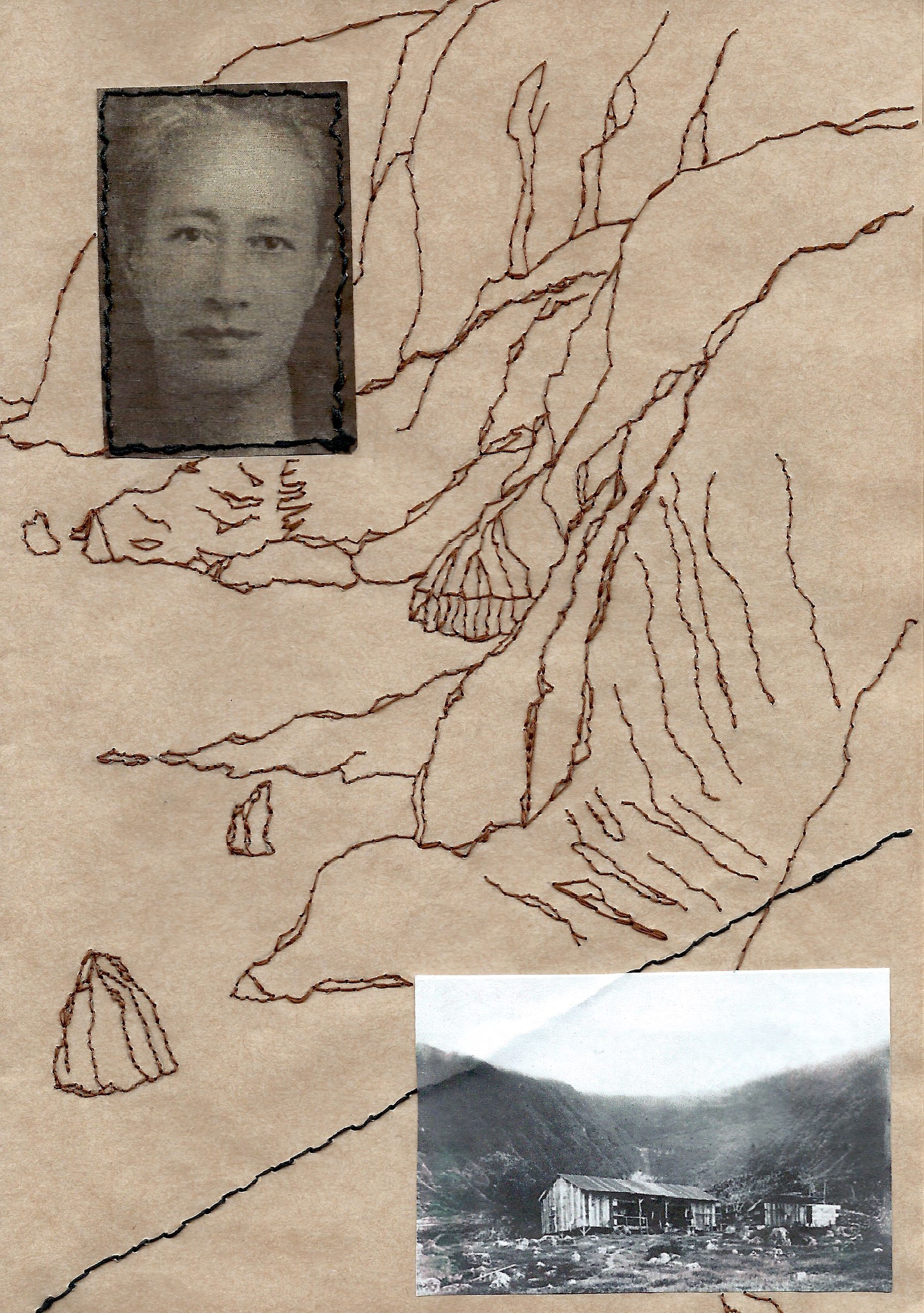

*The beautiful art accompanying “Necessary Gestures” is Isolated By Law—thread, photocopy on stationary paper—by Joy Enomoto. This piece, quite literally, sews together pieces of her past from the cliffs of Kalaupapa to a photograph of her kupuna kuakahi, Annie Keoho and archival photo of a house in Kalaupapa.

HIHumanities’ Love Letters to the Community series is part of our Nā Mana Wai digital publication. This series highlights a diversity of community voices from around our islands and are intended to raise important questions that will lead to continued productive discussion. The opinions expressed here do not represent those of Hawaiʻi Council for the Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.