E Ola, Ka Lani Aliʻi Hope o Hawaiʻi, Ola!

na M. Kawēlau Wright

Lulai 21, 2022

Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole Piʻikoi was born March 26, 1871 in Hoʻai village, Kauaʻi. He was the youngest of three boys born to Princess Kinoiki Kekaulike and high chief David Kahalepouli Piʻikoi. Kūhiō experienced a comfortable early childhood, but faced many hardships as he got older. After his father died when he was just nine years old, his mother moved their family to Honolulu. Once there, Kūhiō and his siblings were named princes and eventual heirs to the Kingdom throne by their aunt and uncle, King Kalākaua and Queen Kapiʻolani, who had no children of their own. Sadly, Kūhiō’s mother died not long thereafter when he was just fourteen years old.

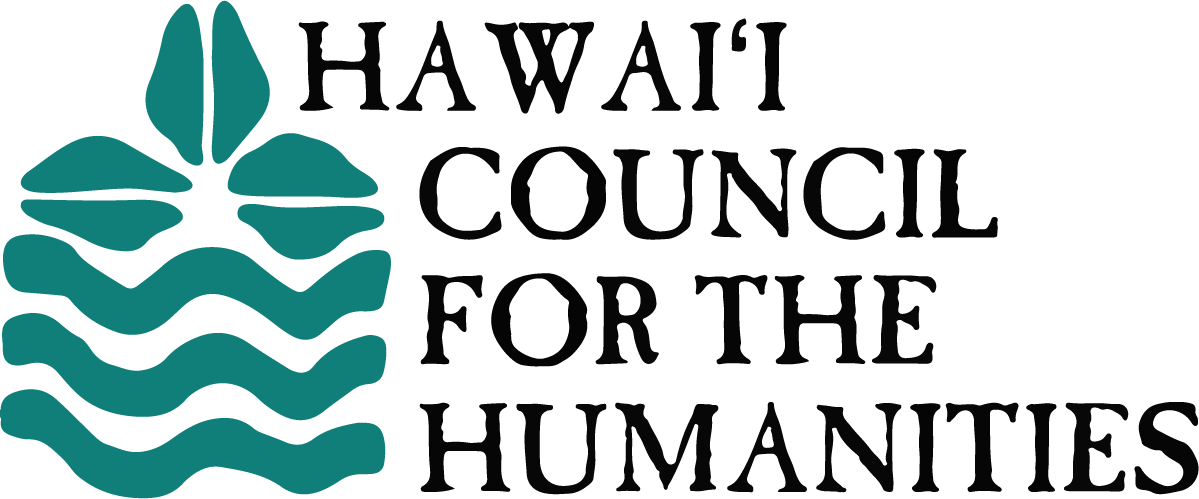

The three princes were adopted by Queen Kapiʻolani and were given the best education available. They attended St. Alban’s School and Oʻahu College, where Kūhiō was a celebrated football star, track runner, rower and bicyclist. In addition to his school-related athletics, Kūhiō was the last aliʻi (chief) trained in the art of lua wrestling and was considered an expert in the holds that were kapu (forbidden) to everyone but aliʻi.

Kūhiō then attended Saint Matthew’s Military Academy in San Mateo, California. During their summer break of 1885, he and his brothers obtained fifteen-foot, 100-pound redwood planks and made them into papa heʻenalu (surfboards), which they took to the Santa Cruz shoreline. A massive crowd came to see the royal brothers as they surfed in the freezing waters, thus introducing surfing to the West coast of America. They did the same in Europe during an 1890 vacation to Bridlington, Yorkshire in England. After his time in California, King Kalākaua sent Kūhiō to Japan where he lived for a year as a guest of the Japanese government. He then studied business at the Royal Agricultural College in England and was hosted in European royal courts while there.

King Kalākaua died in early 1891 and was succeeded by his sister, Queen Liliʻuokalani. Her attempt to install a new constitution was met with a coup led by haole (Caucasion) businessmen with the help of the United States1. After the coup and diplomatic attempts at restoring the Kingdom government, Royalists decided that an armed rebellion was necessary to reseat the Queen and her government. Kūhiō was arrested for his role in this 1895 uprising. A military tribunal found him guilty and sentenced him to one year in prison and a $1,000 fine. The government offered him a reduced sentence or pardon if he identified others that participated, but the loyal 24-year-old refused and was sent to prison.

Kūhiō was released in September of 1895. He married Chiefess Elizabeth Kahanu Kaleiwohi-Kaʻauwai shortly thereafter and they lived in Waikīkī until they decided to leave in response to Hawaiʻi’s increased political uncertainty. They traveled to Africa in 1899, where the prince hunted big game and took part in the Second Boer War. While the couple had the financial means to live abroad, they decided to return to Hawaiʻi for Kūhiō to take on his kuleana (responsibility) as aliʻi serving Hawaiian people. They returned in 1901, after Hawaiʻi was taken by the U.S. as a territory2.

Hawaiʻi’s politics had shifted during their absence. In addition to the Democratic and Republican parties, the Home Rule Party, created by those still loyal to the Queen, was in power. It was assumed that Robert Wilcox, the imcumbmentdelegate to U.S. Congress would again be victorious in the 1902 elections. Initially, Kūhiō had been a supporter of the Home Rule Party, but stepped away because he felt that a delegate from a party familiar to U.S. politicians would have more success than the Home Rule Party that was unique to Hawaiʻi.

The Republicans were assured defeat again by Wilcox, unless they could find someone the native Hawaiian population would vote for. They decided that person was Kūhiō, an aliʻi loved by Hawaiian people. They predicted this love would make Kūhiō a formidable opponent, and convinced him to be the Republican Delegate candidate. Kūhiō believed that his years of diplomatic training would allow him to navigate the U.S. congressional environment and pass initiatives benefiting Hawaiʻi, even as a non-voting member.

The campaign for U.S. Delegate pitted Wilcox and Kūhiō against one another. Hawaiians loved both candidates, but Kūhiō’s political platform focused on his aliʻi lineage. The centuries-long relationship of love and loyalty between Native Hawaiians and their aliʻi was realized in Kūhiō as a possible leader of Hawaiʻi in the U.S. political system. As a result, Kūhiō swept the elections by winning a considerable amount of the white and Native Hawaiian votes.

Kūhiō arrived in Washington, DC in 1903 as Hawaiʻi’s Territorial delegate at a time when racial prejudice was rampant in the United States, and he was often discriminated against and denied service at business establishments. In addition, Kūhiō faced challenges garnering support for Hawaiʻi among U.S. congressmen, which he believed was caused by their collective ignorance. As a result, Kūhiō spent nearly twenty years educating his congressional colleagues about Hawaiʻi. He led in-depth discussions when he and Princess Kahanu entertained them in order to familiarize them Hawaiʻi and its people. Starting in 1907, Kūhiō began hosting congressional party visits to Hawaiʻi to give his colleagues firsthand experiences of Hawaiʻi’s issues and related initiatives that required their votes to pass. As an example, the 1915 visit included thirty-seven members of U.S. Congress, their families, secretaries, and newspaper correspondants. There were one hundred twenty people in total, with the stated purpose of their trip to:

see for themselves what the actual facts concerning the Islands are, how the people live, what are the working conditions of the laboring population, what the port and harbor needs of the Islands might be, the manner in which the chief agricultural industries of the Islands – sugar and pineapples – is conducted, and, generally what the Territory of Hawaii is and could be to the balance of the American Union3.

The party visited different islands in Hawaiʻi and the congressmen were able to see the impacts of Kūhiō’s initiatives firsthand. There were no conditions connected to the visit except that “her congressional visitors come and see for themselves and then legislate concerning Hawaii in the light of personal knowledge of conditions.4” He led these parties in 1907, 1909, 1915 and 1917, and it is likely that many deals were brokered because of Kūhiō’s powers of persuasion as host helping to smooth the way.

Kūhiō introduced many initiatives to benefit the people of Hawaiʻi during his long career in America’s capital. Some details of these follow, but this is by no means an exhaustive list.

Kūhiō created an initiative to dredge and improve Honolulu Harbor in 1903 and struggled to gain enough support in Congress to pay for this project. The congressional visits to Hawaiʻi helped Kūhiō’s efforts in this area by educating the voting members, and after more than ten years, he finally obtained an overhaul to the Board of Harbor Commissioners in 1916, which allowed for harbor improvements in Hawaiʻi.

In 1905, Kūhiō advocated for and obtained an Organic Act amendment creating the system of county governments across Hawaiʻi with their own elected officials which still operates today. This meant that each county could run semi-autonomously, and respond directly to situations affecting the people of their own islands.

Prince Kūhiō tirelessly advocated for Native Hawaiians, contending that they had suffered from European diseases and drastic changes to their culture. In 1914, the prince invited two hundred Hawaiians to his home in Waikīkī for a meeting, and established the organization ʻAha Hui Puʻuhonua O Na Hawaiʻi. This organization created the original plan for the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act (HHCA), which aimed to rehabilitate Native Hawaiians on former Crown and Kingdom Government lands. Kūhiō then used the created plan to introduce the idea of HHCA to the U.S. congress.

Kūhiō also organized a 1918 meeting of forty Hawaiian leaders in Honolulu. This meeting was the start of Hawaiian Civic Clubs that worked with the ʻAha toward passage of HHCA. While Hawaiian Civic Clubs were created to support the HHCA, they have had a long-lasting effect, as over sixty civic clubs still operate today across Hawaiʻi and the United States. These clubs advocate for improved welfare of Native Hawaiians in areas such as culture, health, education and economic development.

It took six long years of negotiations and numerous iterations of the HHCA before it was passed in 1921. While the final version was very different from the original plan, and Kūhiō was reported to have been frustrated by these changes, he did finally see it signed into law.

These are just a few examples of Prince Kūhiō’s work during his time in Washington. As a non-voting member of Congress, he had to rely on his strategic, social and oratory skills, all of which he had gained through his aliʻi training. Ultimately, Kūhiō was elected and served ten consecutive terms from 1902 to 1922, demonstrating Hawaiʻi’s support of their prince. Kūhiō lived his life exemplifying his role as an aliʻi and used his unique training to do what he believed to be best for his people.

Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole was Hawaiʻi’s last aliʻi, and was referred to as both Ke Aliʻi Makaʻāinana (The People’s Chief) and Ka Lani Aliʻi Hope o Hawaiʻi (The Last Royal Chief of Hawaiʻi). Hawaiʻi’s unique history of reciprocal love and honor between aliʻi and their people was evident throughout Kūhiō’s lifetime. He worked tirelessly for what he believed was best for Native Hawaiian people, and while some of the decisions he made were controversial, it is obvious that he was doing what he thought best for his people. The accomplishments featured in this article are just a small example of the extraordinary successes he realized as a non-voting member of US Congress. Many Native Hawaiians have benefitted directly or indirectly from Prince Kūhiō’s efforts, and while we may not agree with everything he did, there is no doubt that he took on the kuleana of an aliʻi and was loved because of it.

1. The coup took place at a time when many Native Hawaiians were experiencing financial problems and social unrest. They pled with their Queen to install a new constitution which would replace the 1887 Bayonet Constitution and its harmful effects on voting rights and cabinet member selection. The handful of haole (Caucasian) businessmen that forced the Bayonet Constitution on King Kalākaua formed a group called the Committee of Safety, and responded to the Queen’s plan for new constitution by collaborating with U.S. representative John Stevens who landed U.S. troops in Honolulu to ensure the Queen stepped down as leader. Thus, through a U.S. backed coup, the Hawaiian Kingdom government was removed from power.

2. It is important to note that the U.S. was never able to pass the required treaty of annexation in Congress, but instead used a joint resolution (a process not used for international matters) to take Hawaiʻi. This action is still actively contested by many.

3. (A Souvenir of the Trip of the Congressional Party to Hawaiʻi in 1915 Booklet | US House of Representatives, n.d.).

4. ibid.

You can find a downloadable copy of Kawēlau’s essay HERE.

Bibliography

Department of Hawaiian Home Lands | Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole. (n.d.)

Hawaiian royals honor Santa Cruz surfing history. (2009, November 25). Santa Cruz

Sentinel.

KALANIANAOLE, Jonah Kuhio | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives.

Martial Law in Hawaii – King Kamehameha V Judiciary History Center

Prince Kūhiō, a prince and a statesman | Honolulu Museum of Art. (n.d.)

Prince Kūhiō: Ke Aliʻi Makaʻāinana – The Citizen Prince. (n.d.-b)

United States, Congress, U. S., Congress; Memorial address (Eds.). (1924). Jonah

Kuhio Kalanianaole: Memorial addresses delivered in the House of

Representatives of the United States in memory of Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole,

late a delegate from Hawaii, Sixty-seventh Congress, January 7, 1923. G.P.O.

Williams, R. Jr. (2021).

Williams Jr., Ronald. Incarcerating a Nation: The Arrest and Imprisonment of Political

Prisoners by the Republic of Hawai’i, 1895. Hawaiian Journal of History, 55(1),

167–176.

Kawēlauokealoha Wright is a faculty member at Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies and a PhD Candidate in the Geography & Environment department at UH Mānoa. She has earned MA degrees in Hawaiian Studies and Geography. Kawēlau’s research includes Hawaiʻi’s Kingdom and Territorial periods with a focus on land tenure and law histories using archival resources.

Kawēlauokealoha Wright is a faculty member at Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies and a PhD Candidate in the Geography & Environment department at UH Mānoa. She has earned MA degrees in Hawaiian Studies and Geography. Kawēlau’s research includes Hawaiʻi’s Kingdom and Territorial periods with a focus on land tenure and law histories using archival resources.

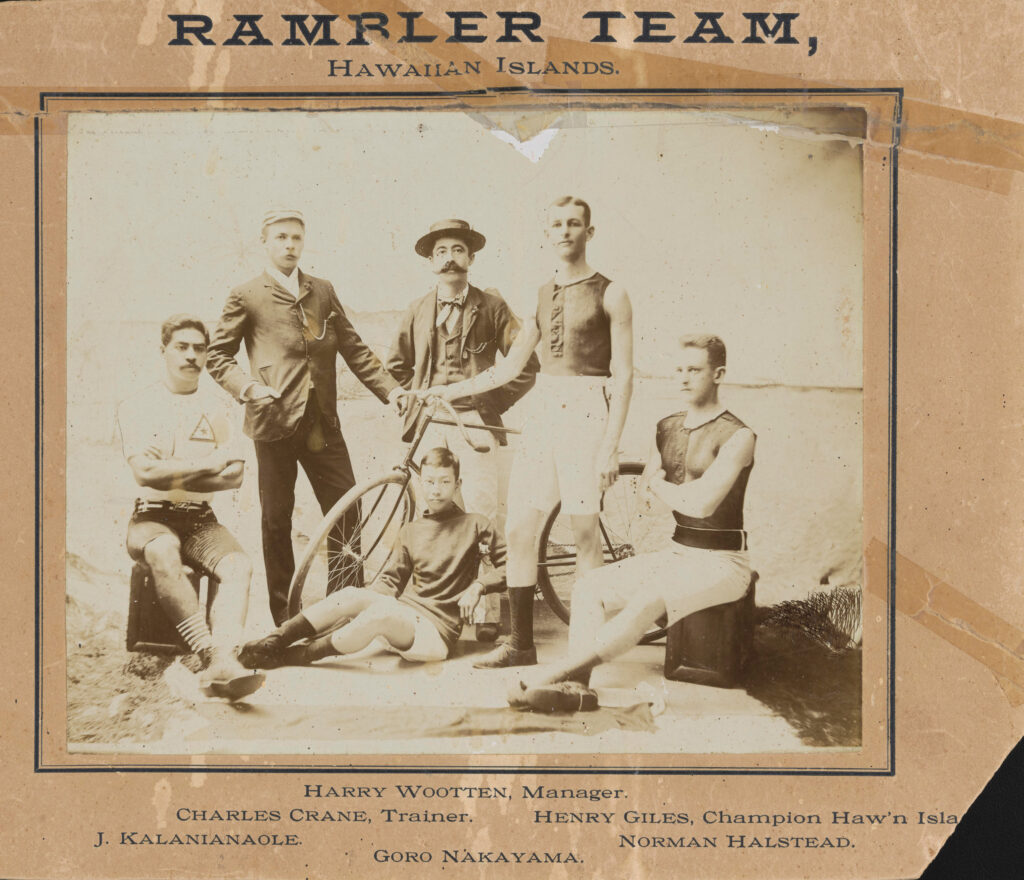

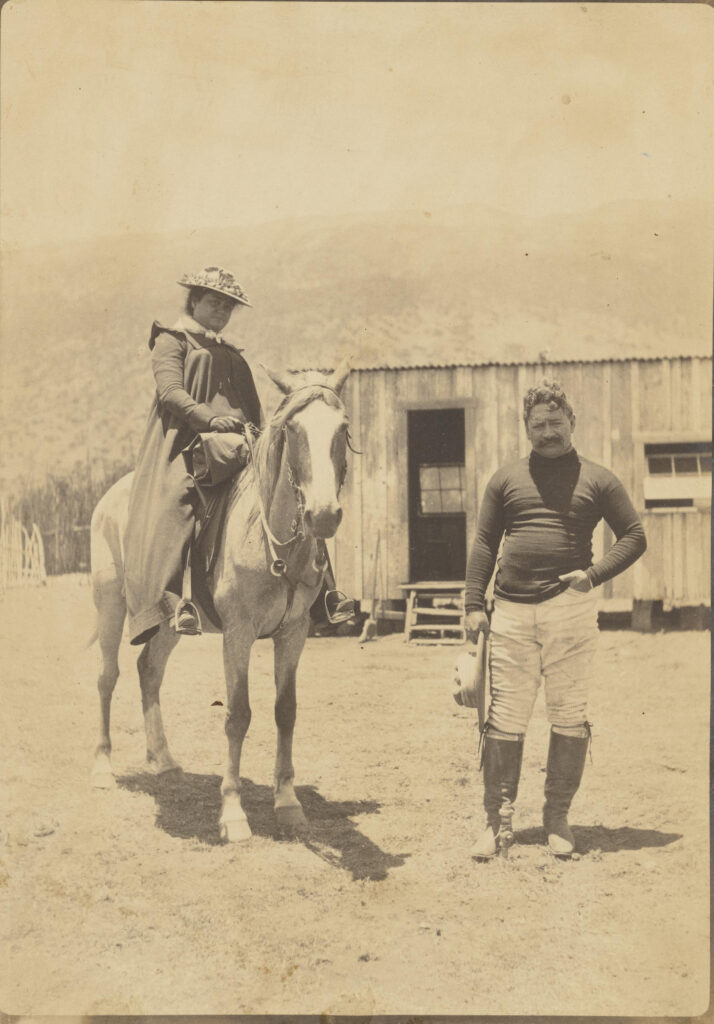

Bonus Photographs of Prince Kūhiō

All photographs of Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole are from the Hawaiʻi State Archives.