Ka moʻopuna i ke alo, The grandchild in the presence

Ka moʻopuna i ke alo, The grandchild in the presence is a short documentary, produced by HIHumanities and directed by filmmaker, Sancia Shiba Nash, honoring the life, work, and legacy of Mary Kawena Pukui, who dedicated her life to perpetuating ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, nā mea Hawaiʻi, and ʻike kupuna.

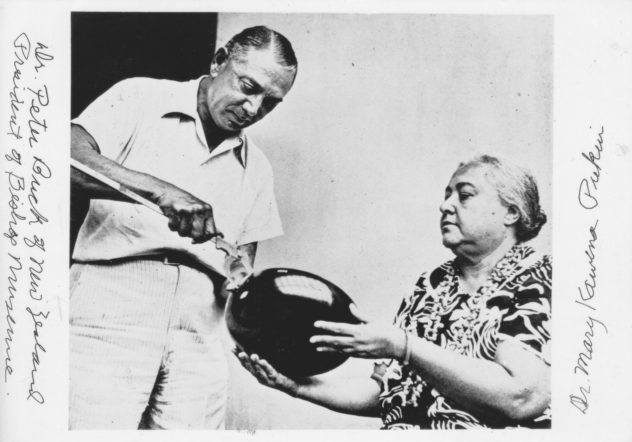

This film touches on some of the extraordinary ways Kawena’s scholarship contributes to the Hawaiʻi of today and tomorrow. Through interviews with her eldest grandson, Laʻakea Suganuma; Kanaka ʻŌiwi scholar Noenoe K. Silva; and Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Historian, DeSoto Brown, we’re given a glimpse into the magnitude of her influence as a scholar, educator and composer. She helped preserve hula kahiko; translated nūpepa, mele, and oli at Bishop Museum; co-authored the 1957 Hawaiian Dictionary; recorded Kanaka Maoli oral histories throughout ka pae ʻāina; and collaborated with social workers at the Queen Liliʻuokalani Children’s Center. Mary Kawena Pukui was the 2020-2021 Honoree of our Hawaiʻi History Day program because of her outstanding leadership in this year’s theme: Communication in History, A Key to Understanding. Kawena’s life-long work drew inspiration from her moʻopuna and was guided by her kūpuna.

She was determined to preserve her mother tongue . . . She said I’m doing this for my moʻopuna and someday yours will benefit too.

L. Laʻakea Suganuma

She was the 20th century embodiment of moʻokūʻauhau consciousness. She was aware that the generations after her, and after us, were going to need this knowledge.

Noenoe K. Silva

Knowledge to me is life. Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono.

Mary Kawena Pukui

A preview of Ka moʻopuna i ke alo, The grandchild in the presence was originally screened across ka pae ʻāina o Hawaiʻi, on April 24th, 2021 for the Hawaiʻi History Day Virtual State Fair.

Mary Kawena Pukui, ke Kāʻeʻaʻeʻa ʻIke Hawaiʻi

na Noenoe K. Silva and Nanea K. Armstrong-Wassel

April 17, 2021

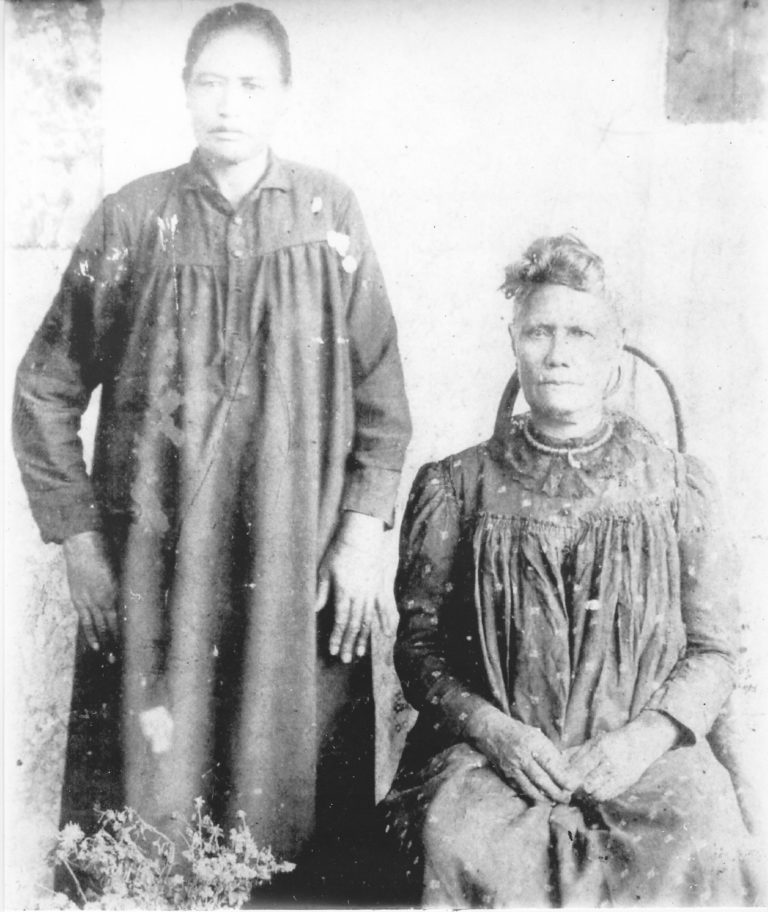

Mary Abigail Kawenaʻulaokalaniohiʻiakaikapoliopelekawahineʻaihonua Wiggin was born in 1895, during the years of struggle between the overthrow of the Native government of Hawaiʻi and the illegitimate annexation of our country to the United States. Her mother was Keliʻipaʻahana (called Paʻahana) Kanakaʻole of Nāʻālehu, Kaʻū, where Kawena was born and raised, and her father was Henry Nathaniel Wiggin of Salem, Massachusetts.

As was the custom among Kanaka families, she was given as hānai to her maternal grandmother, Harriet Hannah Kaʻiakoiliokalanināliʻipōʻaimokuwahinepōʻaimoku, known as Pōʻai. This did not mean that she was separated from her parents, as they all lived near each other in the small village.

Kawena was raised for the first seven or eight years of her life by Pōʻai, and because she was Pōʻai’s first hānai, she was raised as a punahele (favorite). According to Kawena’s own hānai, the late Aunty Pat Bacon, “in those days a punahele child was not resented by other children of the family nor did one hear grumbling about favoritism. [It was] an accepted custom.” She was also raised with a number of kapu that protected her but also kept her separate from other children. No one was allowed to touch her head or hit her in either fun or anger. Because of this, she usually had no playmates, and instead followed her grandmother in her daily activities.

Pōʻai was an extremely knowledgeable kahuna lāʻau lapaʻau (medical kahuna) and pale keiki, or midwife in the traditional Kanaka way. Pōʻai had been raised in a family who were kahu of Pele and kahuna specializing in lāʻau lapaʻau (herbal medicine), kālai waʻa (canoe building), and lawaiʻa (fishing). Pōʻai encouraged Kawena to learn everything and patiently answered her constant questions, always talking to her as if she were an adult. She told Kawena many legends, taught her about the medicinal plants, and allowed her to learn the prayers that were offered while gathering the plants.

Kawena’s family on Paʻahana and Pōʻai’s side were mānaleo, Native speakers of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian), and she too was raised as a mānaleo. She was also raised speaking English and learning English literature from her father. Kawena credited this dual-culture upbringing for her extraordinary ability as a translator.

When she was a child, a group of neighbors would gather once a week when the Hawaiian-language newspaper arrived. One person was chosen to read from the paper aloud, and others would comment on the news and the stories being read. Afterward, people would sing, or recite multiplication tables or other school lessons in Hawaiian, and everyone would join in. In this way, Kawena “learned to chant the lessons as they had been done in the old Hawaiian schools.”

Kawena attended several different kinds of schools as she was growing up. Her favorite was the Catholic school (although her family was Mormon, and sometimes also attended the Protestant church). Father Celestine spoke only Hawaiian to the children, and they were allowed to speak either Hawaiian or English. According to Aunty Pat, “He loved his children and they all knew it and as a result … there wasn’t a better behaved, considerate, thoughtful group of youngsters to be found in the islands.”

When she was older and the family moved to Honolulu, she attended Kawaiahaʻo Seminary (now Mid-Pacific Institute), where the Hawaiian langauge was forbidden. She recounted that she was punished for speaking Hawaiian while trying to help another student, which made her decide to leave school without graduating. She returned to high school in her twenties, graduating from the Seventh-Day Adventist Hawaiian Mission Academy when she was twenty-eight years old.

Kawena Pukui is now widely regarded as the preeminent scholar of Hawaiian knowledge of the twentieth century. Her works include an immense body of translations, including published books such as Daniel Kahaulelio’s Ka ʻOihana Lawaiʻa, Moses Manu’s legend Keaomelemele, and the works of Samuel Kamakau and John Papa ʻĪʻī; hundreds of articles from the ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi newspapers; unpublished manuscripts; and interviews with the holders of ʻike Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian knowledge).

Besides translations, Kawena wrote or contributed to dozens of works documenting Hawaiian knowledge and practices. Her work is crucial because the shift to English in the schools, work places, and government in Hawaiʻi steadily diminished the numbers of people who learned the language, literature, and associated cultural practices from their parents and grandparents. The loss of the language meant a massive loss of knowledge. Kawena felt herself to be a bridge between the generations who were raised in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi with Hawaiian knowledge and the generations who were raised in English. She conducted research in the nūpepa (Hawaiian language papers), interviewed hundreds of knowledgeable people in ‘ōlelo Hawaiʻi, and wrote on many types of Hawaiian practices, including co-authoring The Polynesian Family System in Ka-ʻū Hawaiʻi, Native Planters of Old Hawaiʻi, and Nānā I Ke Kumu volumes one and two. She published papers on Hawaiian games; practices of childbirth, infancy, and childhood; the wahi pana (storied places) of Puʻuloa (Pearl Harbor); songs; ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi; and other subjects.

Besides translations, Kawena wrote or contributed to dozens of works documenting Hawaiian knowledge and practices. Her work is crucial because the shift to English in the schools, work places, and government in Hawaiʻi steadily diminished the numbers of people who learned the language, literature, and associated cultural practices from their parents and grandparents. The loss of the language meant a massive loss of knowledge. Kawena felt herself to be a bridge between the generations who were raised in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi with Hawaiian knowledge and the generations who were raised in English. She conducted research in the nūpepa (Hawaiian language papers), interviewed hundreds of knowledgeable people in ‘ōlelo Hawaiʻi, and wrote on many types of Hawaiian practices, including co-authoring The Polynesian Family System in Ka-ʻū Hawaiʻi, Native Planters of Old Hawaiʻi, and Nānā I Ke Kumu volumes one and two. She published papers on Hawaiian games; practices of childbirth, infancy, and childhood; the wahi pana (storied places) of Puʻuloa (Pearl Harbor); songs; ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi; and other subjects.

Kawena trained as a hoʻopaʻa hula and was recognized as an expert kumu hula and haku mele (composer). She published articles on hula that documented types of dance that are rare today. Three of her articles were published in Hula: Historical Perspectives along with chapters by Dorothy Barrère and Marion Kelly. With Alfons Korn, she collected and translated songs in the volume Echo of Our Song. Seeing the many songs collected by Helen Roberts and Thomas Maunupau in the 1920s, Kawena felt that they should be translated so that many people could enjoy them. Her work resulted in the volume Nā Mele Welo, edited by Aunty Pat Bacon and kumu hula Nathan Nāpōkā, who wrote, “Kawena, with her poetic mind and traditional training in the allusive language of these mele, provided English translations and explanatory notes for most of the chants.”

Kawena created or co-created the standard reference works that everyone with an interest in nā mea Hawaiʻi (anything Hawaiian) uses. First among these is the Hawaiian Dictionary she co-authored with Samuel H. Elbert. Its first publication in 1957 began a reliable system for marking long vowels and the glottal stop in Hawaiian, which are necessary to accurately represent the sounds and meaning of words in the language. The 1986 edition of this dictionary remains the standard source for definitions and spelling of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi. Her work also contributed to Place Names of Hawaiʻi, which remains the first source for organizations like the Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names. That board determines the correct spelling of place names for the State of Hawaiʻi and United States Geological Service.

ʻŌlelo Noʻeau: Hawaiian Proverbs and Poetical Sayings, published after Kawena passed into the pō, might be considered her masterpiece. Kawena began collecting ʻōlelo noʻeau when she was just fifteen years old. The book we have today contains nearly 3,000 poetic sayings. This compendium is an essential work for understanding almost any prose spoken or written in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi by mānaleo born prior to 1960 or so. Proper ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi must make use of figurative sayings or is considered poor speech or writing. Kawena’s work in gathering, translating, and explaining these thousands of sayings helps us not only to understand what mānaleo said and wrote, but careful study teaches us how they thought. It teaches us, for example, that love and beauty are described using terms having to do with ʻāina (land). For example, “A ʻai ka manu i luna. The birds feed above. An attractive person is compared to a flower-laden tree that attracts birds.” Another is “Pali ke kua, mahina ke alo. Back straight as a cliff, face bright as the moon. Said of a good-looking person.”

Much of Kawena’s work at the Bishop Museum was in support of various anthropologists, including E. Craighill Handy and Elizabeth Handy, who credited her as co-author and Kenneth Emory, among others, and the folklorist Martha Warren Beckwith. Beckwith could not have produced any of her works of translation, including Kepelino’s Traditions of Hawaii and The Kumulipo without Kawena’s translations and corrections. Kawena was an indispensable researcher with Margaret Titcomb on the fishes, dogs, and ʻawa of Hawaiʻi nei.

Kawena created one the most valued tools for researchers of ʻike Hawaiʻi, the Hawaiian Ethnographic Notes at the Bishop Museum Archives. This work indexes hundreds of articles of the nūpepa and from the manuscript collection of the Archives. It catalogs her own unpublished essays, lectures, and translations. Every researcher is grateful for this work done over many decades that Kawena has gifted us with.

Mary Kawena Pukui was recognized for her immense knowledge and lifetime of contributions to ʻike Hawaiʻi. She was named a Living Treasure of Hawaiʻi in 1976; inducted into the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame in 1995; awarded a University of Hawaiʻi Doctor of Letters in 1960 and a Doctor of Arts and Letters by Church College of Hawaiʻi in 1974; and nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1981.

Kawena’s grandmother, Pōʻai, was her first source of knowledge of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, Hawaiian cultural practices, and the world around her. Because of this intergenerational passing of knowledge, and because of the English language education she first received from her father, Kawena considered herself a bridge between generations, and between cultural and linguistic gulfs that separate people in Hawaiʻi. She not only knew the importance of history as recorded in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, she embodied the slogan “mālama our history, mālama each other.” Her entire life was spent in treasuring, collecting, composing, and translating ʻike Hawaiʻi, so that we and all future generations may better understand the Kanaka world we live in.

Works Consulted

Bacon, Pat Namaka, and Nathan Nāpōkā. “Mary Kawena Pukui.” Lecture, Peabody Museum, Salem, MA, October 15, 2005.

Bacon, Pat Namaka, Helen H. Roberts, and Nathan Napoka, eds. Nā Mele Welo – Songs of Our Heritage: Selections from the Roberts Mele Collection in Bishop Museum. Honolulu. Translated by Mary Kawena Pukui. Bishop Museum special publication 88. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1995.

Mary Kawena Pukui Cultural Preservation Society. https://marykawenapukui.com/

Osorio, Jamaica Heolimeleikalani. “(Re)membering ʻUpena of Intimacies: A Kanaka Maoli Moʻolelo Beyond Queer Theory.” PhD diss., University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2018.

Pukui, Mary Kawena, George Bacon, and Patience Nāmaka Bacon. “Untitled Biography of Mary Kawena Pukui.” Honolulu, Bacon Family.

Schütz, Albert J. Hawaiian Language: Past, Present, Future. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2020.

Silva, Noenoe K. and Nanea K. Armstrong-Wassel. “Introduction.” In Knowledge Is Life: Selected Essays, Interviews, and Lectures of Mary Kawena Pukui, eds. Noenoe K. Silva and Nanea K. Armstrong-Wassel. Forthcoming from Kamehameha Publishing and Bishop Museum Press.

Williamson, Eleanor Lilihana-a-I. “Introduction.” In ʻŌlelo Noʻeau: Hawaiian Proverbs and Poetical Sayings, by Mary Kawena Pukui, xi-xix. Bishop Museum Special Publication 71. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1983.

Selected Bibliography of Works by Mary Kawena Pukui

Barrère, Dorothy B, Mary Kawena Pukui, and Marion Kelly. Hula: Historical Perspectives. Pacific Anthropological Records, no. 30. Honolulu, Hawaii: Dept. of Anthropology, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, 1980.

Elbert, Samuel H., and Mary Kawena Pukui. Hawaiian Grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1979. https://www.ulukau.org/elib/cgi-bin/library?c=hawaiiangrammar.

Green, Laura S., and Mary Kawena Pukui, eds. The Legend of Kawelo: And Other Hawaiian Folk Tales.Honolulu, T. H, 1936.

Handy, E. S. Craighill, Elizabeth Green Handy, and Mary Kawena Pukui. Native Planters in Old Hawaii: Their Life, Lore, and Environment. Rev. ed. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin 233. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1972.

Handy, Edward Smith Craighill, and Mary Kawena Pukui. The Polynesian Family System in Ka-‘u, Hawaiʻi. Rutland, Vt: C. E. Tuttle Co, 1972.

Ii, John Papa. Fragments of Hawaiian History. Translated by Mary Kawena Pukui. Rev. ed. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Special Publication 70. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1983.

Kahaulelio, Daniel. Ka ʻOihana Lawaiʻa: Hawaiian Fishing Traditions. Edited by M. Puakea Nogelmeier. Translated by Mary Kawena Pukui. Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: Bishop Museum Press and Awaiaulu Press, 2006.

Kamakau, Samuel Manaiakalani. Ka Poʻe Kahiko – The People of Old. Edited by Dorothy B. Barrère. Translated by Mary Kawena Pukui. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Special Publication 51. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1964.

———. Tales and Traditions of the People of Old – Na Moʻolelo a Ka Poʻe Kahiko. Edited by Dorothy B. Barrère. Translated by Mary Kawena Pukui. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1991.

———. The Works of the People of Old – Na Hana A Ka Poʻe Kahiko. Edited by Dorothy B Barrère. Translated by Mary Kawena Pukui. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Special Publication 61. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1976.

Manu, Moses. Keaomelemele: He Moolelo Kaao no Keaomelemele. Translated by Mary Kawena Pukui. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 2002.

Pukui, Mary Kawena. ʻŌlelo Noʻeau: Hawaiian Proverbs & Poetical Sayings. Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: Bishop Museum Press, 1983.

Pukui, Mary Kawena, translator. Nā Mele Welo – Songs of Our Heritage: Selections from the Roberts Mele Collection in Bishop Museum, Honolulu. Edited by Pat Namaka Bacon, Helen H. Roberts, and Nathan Napoka. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1995.

Pukui, Mary Kawena, and Samuel H Elbert. Hawaiian Dictionary: Hawaiian-English, English-Hawaiian. Rev. and enl. ed. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1986.

Pukui, Mary Kawena, Samuel H. Elbert, and Esther T. Mookini. Place Names of Hawaii. Rev. and enl. ed. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1974.

Pukui, Mary Kawena, E. W. Haertig, and Catherine A Lee. Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source). 2 vols. Honolulu: Hui Hanai, 1972.

Pukui, Mary Kawena, and Alfons L. Korn, eds. The Echo of Our Song: Chants & Poems of the Hawaiians. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1973.

Sancia Shiba Nash is a filmmaker and artist from Honuaʻula, Maui. Through time-based media, primarily video and sound, she helps to amplify lesser-known transpacific stories of place. Oral history interviews and private/public archives provide the foundations for her collaborative practice.

Noenoe K. Silva is from Kailua, Koʻolaupoko, Oʻahu, and teaches politics and ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi at UH Mānoa. Through her knowledge of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, she brings to light the scholarship, wisdom, and understanding of Native Hawaiian writers, artists, and political activists of the past.

Nanea K. Armstrong-Wassel is a Hawaiian Cultural Research Specialist with Hoʻokahua at Kamehameha Schools and the current Curatrix at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Heritage Center. She was a former research specialist at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Library and Archives and still remains a volunteer there until this day.

Mahalo Piha

So many people gave their aloha to make this honoring of Mary Kawena Pukui possible. We are so grateful to everyone for their deep and abiding sense of mālama for our history.

Laʻakea Suganuma, of the Mary Kawena Pūkuʻi Cultural Preservation Society, generously donated family photographs and beautiful moʻolelo about his times with his grandmother. His love for his ʻohana and future generations inspires us.

Noenoe K. Silva co-wrote “Mary Kawena Pukui, ke Kāʻeʻaʻeʻa ʻIke Hawaiʻi” and was interviewed for Ka moʻopuna i ke alo, The grandchild in the presence. Her dedication as a kumu and historian makes so much possible.

Nanea K. Armstrong-Wassel co-wrote “Mary Kawena Pukui, ke Kāʻeʻaʻea ʻIke Hawaiʻi” and was so generous with her time from the very beginning of this project. Her stories set our path.

Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Library and Archives supplied access to audio, visual, and print material, and we thank the many hands who take care of such precious stories.

Hawaiʻi State Archives provided photographs.

ʻUluʻulu: The Henry Kuʻualoha Giugni Moving Image Archive facilitated accessing archival footage. Mahalo for helping us navigate the waters.

Hawaiʻi Public Broadcasting Service gave us permission to use footage from A Retrospective to Mary Kawena Pukui.

Sancia Shiba Nash directed and edited Ka moʻopuna i ke alo, The grandchild in the presence. Her commitment to this project was profound and humbling.

And mahalo nui loa to our co-sponsors in launching this beautiful film out into the world. Thank you for spreading the word!

Nā Mea Hawaiʻi

Kanaeokana

Hawaiʻi Women in Filmmaking

Kāhuli Leo Leʻa

Honolulu Museum of Art

Bishop Museum

Kamehameha Publishing

The Mary Kawena Pukui Cultural Preservation Society