Lee Tonouchi, deeply involved and committed to the Hawaiʻi literary community for over three decades, has won the Tony Quagliano Poetry Award.

With cutting tenderness, voice, and masterful craft, Lee Tonouchi’s poems enact inversions and reconfigurations—playful to serious to provocative—that shape a vital heart of living Pidgin in Hawaiʻi.

—J. Vera Lee

Judge for 2021-2022 Tony Quagliano Poetry Award

Hajichi: Tattoos and Diamonds is Forevah

I cannot tell

if her hands shaking

cuz she nervous

dat going hurt

or if it’s cuz

of da forbiddeness

of her ack,

dat she’s here despite

her fiance’s wishes.

Like us,

her fiance’s one Local

Okinawan too

but he’s not down

wit da whole idea.

He said getting da tops

of her hands

tattooed is barbaric,

and he equated da practice

to branding

and treating women

like possessions.

Ironically,

he suggested he

could create one design

for her

instead.

I come involved

when she calls me up

and asks me if I

know anyting

about hajichi.

I tell her I no tink

it’s about da husband

doing ‘em to da wife

saying you belong to me,

and I share wit her

da Okinawan myth

my grandma toll me,

da one about da princess

who marked her hands

so dat her pirate capture,

whose personal preference

wuz for hands

sans anykine markings,

would find her repulsive

and set her free.

I tell her

to me, da story’s

about how da princess

uses her ingenuity

for defeat one more mighty-er

enemy.

Togeddah we

do sa’more research,

wea we learn right around da turn

of da twentieth century

da Japan government

using military force

invaded

and took control

of independent Okinawa.

As time went on, our ancestors

loss control ova

their government,

their lands,

their culture.

An’den da Japan government

banned

da shaman women of da villages,

who did da hajichi tattoos,

from practicing their artform,

in order for allow for one more

homogeneous culture

and easier assimilation

of Okinawans into Japan.

Some Okinawans believed

dat da hajichi ban

wuz one excuse

for round up and imprison

da Okinawan women elders

and break up

their power.

Yet,

despite da fack

dat their culture wuz one crime

many Okinawan women

still continued for get

their hajichi,

as their act

of

resistance.

As my friend passes da photo

of her great grandma’s hajichi

to da tattoo artist.

I tell her she lucky she get

dat photo.

I ask her

one more time if she sure.

If she sure, she sure.

Cuz what if her husband-to-be

calls off da wedding?

I remind her dat both

tattoos and diamonds

is forevah.

She looks at da back

of her hand

as she reminds me

dat even in Okinawa

hardly get any women

wit hajichi anymore.

So even though her fiance

might not like how it looks,

it doesn’t matter

what he thinks,

because to her

it’s

beautiful,

it’s very beautiful.

I note da steadiness,

in her hand,

as she extends her arm

and flips her wrist

so dat da top of her hand

faces outward.

I note da steadiness

in her voice

when she declares,

“If he

don’t like it,

he

can talk

to da hand.”

Palms Face Up

I ask my Grandma hakum

in every family picture

Obaban stay sitting down

with her hands on her lap

wit her palms face up.

Grandma sez

when Obaban came Hawai‘i

she wuz shame

cuz none of da oddah women

had dat kine

Okinawan tattoos

on da backs of their hands.

Das why whenevah she went out

no mattah how hot,

she always

wore gloves.

Obaban even toll Grandma

dat when she she ma-ke time

make shua her hands

get da glove on

when she stay in da casket.

Grandma sez

she made her promise.

I ask Grandma

if Obaban wen stay in Okinawa

den would she have been

not shame?

Obaban wuz probably

embarassed

before she came wuz,

Grandma tells.

Because back in Okinawa

everyting Okinawa

wuz coming shame.

Grandma tells me

she heard stories

dat in da schools ova dea

if dey caught you speaking

Uchinaguchi

you had for wear

da hogen fuda sign

around your neck

as your punishment

marking da fack

da way you spoke

wuz inferior.

I still no get it.

How can? I ask.

How can be shame Okinawa

when you

IN

Okinawa?

“When Japan took over

Okinawa

dey teach

Okinawa way

not da right way.

Dey teach,

you gotta be like

da mainland.”

“Like da ‘mainland,’”

I repeat.

And das when

all of a sudden

I can relate li’dat,

you know da kine.

To read the rest of Lee’s Tony Quagliano Award Winning Poems click HERE.

Reading Tonouchi’s work is like being invited to share in the supple imagination of a maker. His poems, immersive, layered, mischievous, dart around with an intense energy, circling and recasting loss, survival, and intimacy in a community and world made of Pidgin.

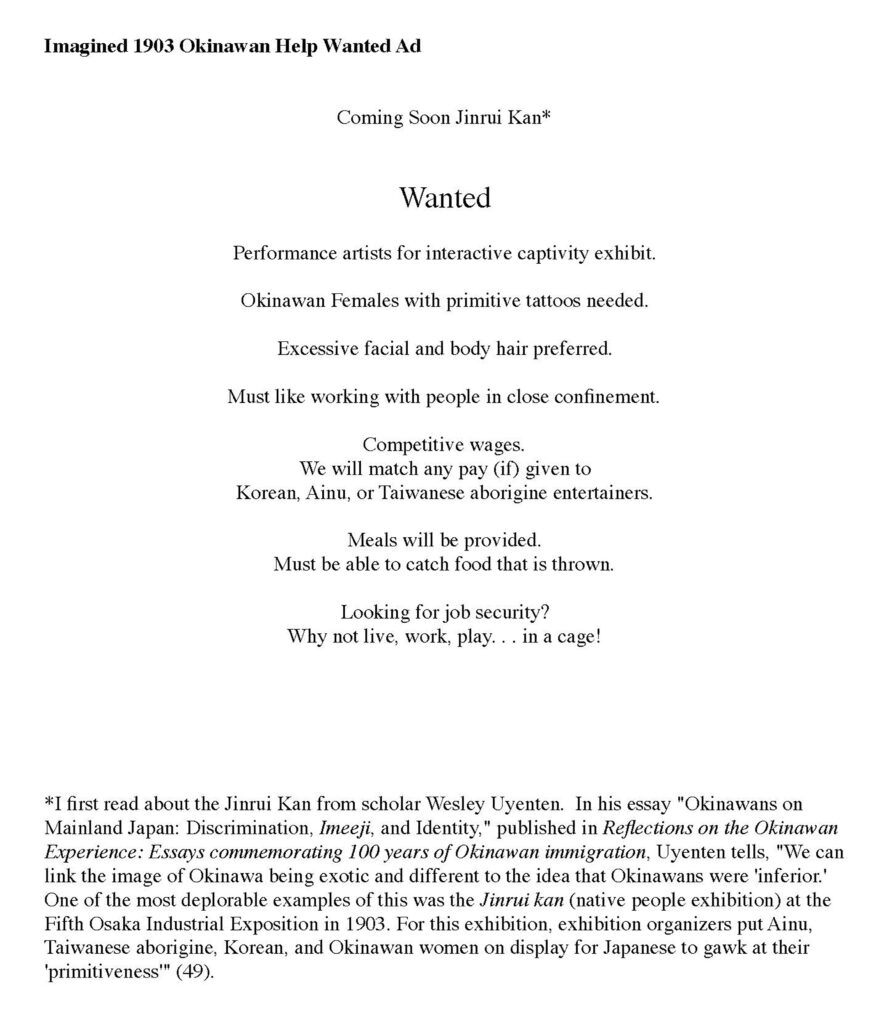

Tonouchi’s “Imagine 1903 Okinawan Help Wanted Ad” launches a through-line of otherness and the question of performativity: Where does it happen? and Where does it end? Written primarily in Pidgin, Tonouchi’s poems resist oversimplification, unwilling to offer easy virtue or a moral high ground to the reader as even the speakers’ positions shift throughout the work. This perspectival joinery would give rhythm to stories, really the work of life per Tonouchi’s vision. Like N. Scott Momaday (in The Way to Rainy Mountain) Tonouchi has a gifted ear for tonal shifts and mimicry. Not only does he admit that to learn a language is to learn that you don’t need to learn it (“Uchinaaguchi Paradox”), he also makes deft work of juxtaposing quotation and interior monologue so that his poems – multi-vocal, to say the least – get at the details of militarization, from its justification to its micro-presence in Oahu vis-a-vis televised heroes (“McGarrett Would Go”) to tone deaf television/government-speak disregard for a labor force (“Hawai’i’s most Dangerous Job”).

Nor does Tonouchi fall into and out of Pidgin to perform identity. Rather intimacy (shared with us) means – as lifeblood – this is how I know myself/a self, and Tonouchi’s image sets root and grows over timed in our imagination:

No go by da pokey pokey plant.

Abunai, da plant

Poison.”

So I always wondered

How come dey went plant that for den?

Curious, I see da pokey pokey plant

….

On da oddah hand it also signifies, Eh, we made it.

Dis house that we worked hard for buy

Is one Okinawan house

And DIS is our flag. (“How You Can Tell One Okinawan House”)

That is, consciousness turns on a flag, or even a “plaque” – perhaps a subject rhyme for “hogen fuda” – each seemingly static surface does both the inventive and self-reflexive work of marking Okinawan. That Tonouchi has worked tirelessly to increase the visibility of Okinawan literature makes a rich and consistent layer in his work.

“Like da ‘mainland,’” I repeat.

And das when

all of a sudden

I can relate li’dat, you know da kine. (“Palms Face Up”)

And yet his approach to questions about marginalization, or militarization or colonization for that matter, is nimble, telescoping out and zooming in as a matter of distance and intimacy and also as an expression of humor. His awareness twists to and on us. If “Palms Face Up” [to hide one’s tattoos] lends itself to a memory of “da hogen fuda sign” to shame Unchinaaguchi speakers, tattoos in “Hajichi: Tattoos and Diamonds is Forevah” ends with “If he/don’t like it, he/ can talk/to da hand.”

As a non-Pidgin speaker reading Tonouchi’s Pidgin poems, I wondered where my curiosity could safely land. How close could I get to the poems? And yet Tonouchi’s prismatic language and forms – with great resolve and beauty – generously enlarge the range of the poet’s condition to the human condition. And to my ear, the twisting and twining of tropes and images is most poignant in “Okinawan Proverb.” Perhaps because it starts with an origin claim “Okinawa means “rope in the open sea” and undulates across the page – well, one hopes the form holds its tension but the sense of effacement feels inevitable. A rope in the water can only be held taut when it is held – or Tonouchi has held out attention rather taut with his poems by breathing life into Okinawan beliefs and language with his offering.

—J. Vera Lee

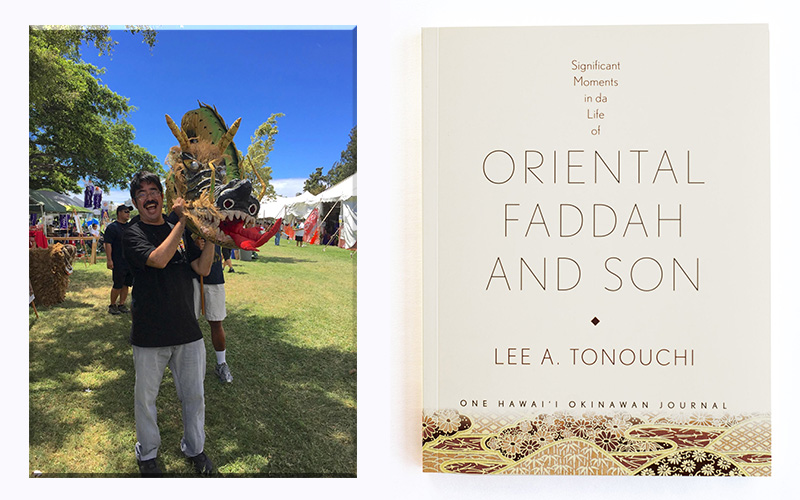

Lee A. Tonouchi stay known as “Da Pidgin Guerrilla”. His Pidgin poetry collection Significant Moments in da Life of Oriental Faddah and Son: One Hawai’i Okinawan Journal won da Association for Asian American Studies Book Award. His oddah books include Da Word, Living Pidgin, Da Kine Dictionary, Buss Laugh, and Okinawan Princess: Da Legend of Hajichi Tattoos dat won one Skipping Stones Honor Award. He had plays produced before by Kumu Kahua Theatre and da Honolulu Theatre for Youth. An’den East West Players did his Pidgin play Three Year Swim Club which wuz one Los Angeles Times Critic’s Choice Selection.

Lee A. Tonouchi stay known as “Da Pidgin Guerrilla”. His Pidgin poetry collection Significant Moments in da Life of Oriental Faddah and Son: One Hawai’i Okinawan Journal won da Association for Asian American Studies Book Award. His oddah books include Da Word, Living Pidgin, Da Kine Dictionary, Buss Laugh, and Okinawan Princess: Da Legend of Hajichi Tattoos dat won one Skipping Stones Honor Award. He had plays produced before by Kumu Kahua Theatre and da Honolulu Theatre for Youth. An’den East West Players did his Pidgin play Three Year Swim Club which wuz one Los Angeles Times Critic’s Choice Selection.

You can find him on Facebook facebook.com/leetonouchi and Instagram—@pidginguerrilla.

J. Vera Lee has lived in Honolulu for over a decade. Recently her work appeared in Joyland, New American Writing, and Second Factory. She is the librarian at the Honolulu Museum of Art.