[All of these gorgeous illustrations are by the author, and reproduced with permission and gratitude.]

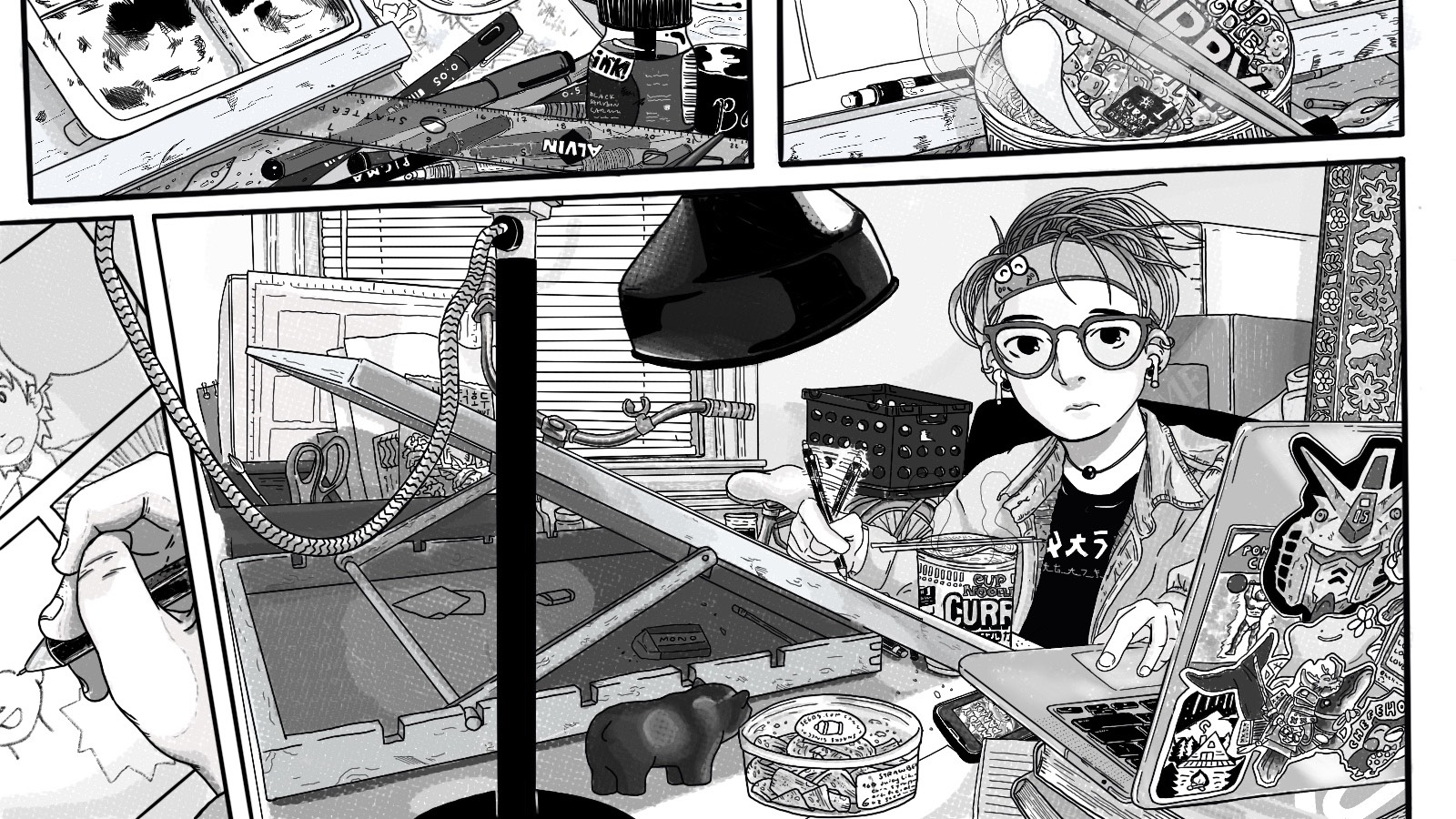

It seems uncanny that the latest graphic memoir by legendary cartoonist Adrian Tomine, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, hit shelves five months into a global pandemic, a time where many of us know a thing or two about what it means to feel insanely, inconsolably lonely. In the book, cleverly and satisfyingly designed to mimic a Moleskine right down to the grid paper pages and elastic cover-fastener, Tomine chronicles his hero’s journey as the “boy wonder of mini comics” in small, awkward moments that form the path between his first scathing magazine review to his reign as a New York Times best selling author and beyond. Most striking to me, who relates strongly to Tomine on the basis of being a cartoonist with a Japanese last name no one wants to pronounce, is that throughout the panels, and deep within the gutters of his narrative, dwells the promise that the payoff for his years of solitude is the opportunity to rejoin the rest of the world, as if his success is inextricably tied to his access to others. Although unafflicted by the pressures of fame that plague Tomine, I don’t need praise from Alan Moore to know self-doubt and loneliness. Now more than ever, the view from above my drawing station and behind my iPad looks slightly more desolate than when I first picked up my pencil and decided to draw.

At the advent of social distancing, I may have said this solitary existence would be the dawn of the age of artists, myself included; a cave-dwelling nerd person who has spent an abbreviated lifetime cultivating stay-at-home hobbies. But unlike my kid brother, living undisturbed in the virtual reality of the video gameverse, I am not fifteen anymore, and an indeterminate stay-at-home-future melted into a soup of liquified time. If you will indulge me in this metaphor: the panels of my time-tabled life collapsed and everything once contained within lines of normalcy bled together. Even the things I had to do (final papers, virtual graduation events, and interning with Hawaiʻi Council for the Humanities), could not lego brick themselves into the semblance of a schedule. I questioned what skills I had gained from spending my childhood holed up in my bedroom drawing Dragon Ball characters again and again, begging for the sweet mercy of a privacy rarely afforded the oldest of three siblings. Clearly, the ability to exist within a vacuum was not one of them.

As much as I could write this off as a lamentation of my unmotivated self, this isn’t about how lethargy replaced my muscles with jello, or how my sleep patterns reversed to that of a newborn baby. Instead, as I reflect on my decision to embark on a master’s degree in public humanities, I think about how I, an anime-watching, manga-reading, emo kid from Hilo, figured out how to merge with this robust field of academics and public practitioners on my own terms. During my internship with HIHumanities, I have been presented with challenges; chances to showcase the confluence of influences from which my work, both academic and creative, derives. These tasks, along with the atmosphere brought by the pandemic and the psychological effects of social distancing, have encouraged me to focus my energies into the things that bring me joy, and just as importantly, to consider how those things allow me to overcome the loneliness of long-distance cartooning.

Time warp to when I was in middle and high school and it seemed to be the utmost concern of my teachers that we younglings be able to locate and adequately describe our wahi pana, explained to us as a haven or somewhere we could find meaning. Innumerable poems, personal essays, and artwork of all mediums were composed for many a grandmother’s house, secret surf spot, and backyard loʻi. Looking back, I think our wahi pana was never meant to be defined by the physical or spatial, but as the state of joy brought upon by entering a certain environment or recalling a certain memory that brings us a sense of peace. But because I was incurably strange, an affliction brought upon by listening to whiny midwest white boy music and playing Academic Decathlon, I just had to make my wahi pana, if I remember correctly, “the dark abyss of my troubled mind.” I share a collective eye roll with you, dear readers.

This place was a lot less troubled than my teenage-self would argue, and it was quite the opposite of dark. If you were to ask me now and if I had been honest then, my wahi pana was at my desk, perched above my ink stained drawing board, sketching original manga to the soundtrack of mid-2000s pop punk, while crushing the sweet/sour chalk of lemon Pez on my tongue. I spent hours drawing for the satisfaction of no one but me. Devoid of constraints and without the scrutiny of onlookers I surrounded myself with characters I birthed in graphite and India ink, who carried in their paper hearts wondrously fictional lives and loves. I was generous to myself, as nonsense-filled sketchbooks piled in my room and page by incoherent page unburdened my teenage mind—still unjaded and waterlogged with imagination. Perhaps, like Adrian Tomine, I was lonely, but that was a small price to pay if it meant flying high on an ambrosia of inspiration. The abyss came later, and when the chasm split from under me, it was as long and deep as my first two years of college, by the end of which I had a 0.5 GPA and was only allowed to enroll for another semester at UHM by the divine grace of a clerical error. I had stopped drawing and only read enough comics to remind myself I was literate. I inhabited spaces, be it behind an espresso bar or in the insincere arms of a lover, but I had long lost the way to my wahi pana and its feeling of limitlessness.

Time warp to the spring semester of my sophomore year, barely hanging on by a thread, I made two decisions that at passing glance might seem inconsequential; I picked the right class and the right comic. The class, Asian American Literature: Comics and Graphic Novels with professor Shawna Yang Ryan, completely shook up my brain and expanded my understanding of what comics could be: vessels for cultural exchange, keepers of history, implements of empathy. The comic was My Hero Academia, the now worldwide phenomenon about teenage heroes fighting to stand out and rise above in a world where nearly everyone is born with supernatural abilities. For the first time in years, I could feel my heartbeat flutter like pages between my fingers, and my ambivalent sense of being was overtaken by the desire to enter these worlds where I could feel entirely unconstrained by reality. I felt like a child discovering what it means to truly love something. This reignited passion, combined with my newfound direction to connect manga with ethnography and history, led me to a place I had not been in a long time. If I could convince my professors to allow it, I wrote papers about comics or papers as comics, and for the first time, since I was in high school, I transmuted inspiration into unbound creation. Today, I write, draw, and study how comics, as a form, affords opportunities for cultural immersion, exchange, and preservation, especially in Native Hawaiian and other Indigenous communities. The misconception that wading through academia meant parting the seas between the supposedly immature (read: things I actually love), and the testament of the canon (read: the things I thought I had to love to be successful) blew me off course, and it took years to reorient myself on the journey to re-find my wahi pana. I was just lucky that after all that time, I hadn’t lost the key, and the pocket of joy that provided me a safe haven in my youth had not forgotten or forsaken me.

Time warp to early 2020: if you can picture a gender-ambiguous mass with aggressive side bangs in a blue peacoat sliding down the iced streets of Providence, Rhode Island in early February, you would be following me to a Swedish pastry shop on the corner of Angel and Main streets and the serendipitous meeting I had with R. Kikuo Johnson, one of my idols. When I first read his book, Night Fisher, at the BOOK OFF in the now demolished Ward Warehouse, I knew that I was holding in my hands the clearest blueprint to what a comic set in contemporary Hawaiʻi could look like. Fast forward to sitting across from the author/illustrator himself, separated only by a hot cocoa, jasmine tea, and thousands of hours of experience, I attempted to chip away at the distance between us with questions about writing, storyboarding, and publishing. The one gift of wisdom that still catches on my insecurities now and then. “You must be able to stand drawing in an empty room by yourself day in and day out, again and again, obsess over every little line, mark, and detail until your vision is realized on the paper before you; if you’re not ready to be in that mental state then you’re not ready to write your graphic novel.” (Quotes attributed to Kikuo Johnson in this piece may be dramatized to compliment my desire to be spoken to like a manga protagonist.) In any case, I remain in a state of wanting to both prove him wrong and prove him right—of wanting to show him I have what it takes, but also that there must be a different way than the path through which he and Tomine found success.

Time warping back to the public health apocalypse that is today, I don’t even need to explain how a comic book, no matter how comforting, will never be enough to patch the wound opened by the reality of social distancing and shelter in place. Even the most hermitted among us have not been immune to the harshness of the Covid-19 fallout, and although skimming through a volume of Spy x Family (10/10 manga, I recommend) or sketching a daily journal had been enough to keep me going, I became consumed by the solitude seeping into the corners of my apartment thousands of miles away from home. The difference was that not only did the commitment to my new field of public humanities force me to think about how to defy the odds and connect to others, but also that I had mastered the ability to slip in and out of my wahi pana state easier than Goku turning Super Saiyan. Amplified by the opportunities gifted to me through my summer practicum with HIHumanities, I set out to transcend the way I used comics as a medium of exchange. I asked, how can the graphic form serve the non-comic loving public?

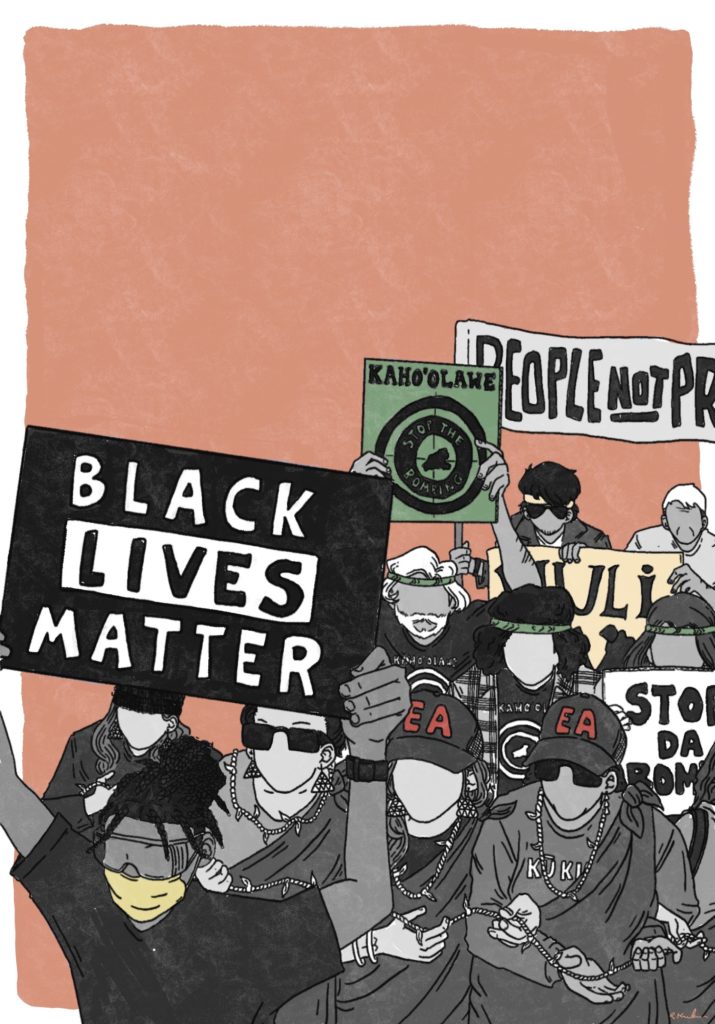

Cartooning is not a solitary experience. I mean no disrespect to Adrian Tomine when I say this, but if my short time at HIHumanities has taught me anything, it is that the most meaningful works are made in collaboration with and in consideration of others. In designing my first project, the poster for a Try Think event entitled “Why is protest a bad word?” I grappled a lot with the idea of how my illustration, especially about a topic so charged with tension, would come across to the general public. The decision to feature protestors from the Black Lives Matter movement followed by those from Hawaiʻi’s most consequential resistance movements was an attempt to appeal to people, perhaps skeptical of BLM, who might recognize symbols of our own local history, make the connections between them, and feel inspired to ask questions.

I thought about the way this image would serve as the precursor, the appetizer if you will, to the actual event, and how it might incite conversation. While I must admit, I drew this in solitary confinement—the 14-day mandatory quarantine to be exact—I approached the project in a way that made it impossible to feel alone, because I found myself standing in the confluence of two powerful streams, the stories of those immortalized in illustration and the eager public swirling with the energy of curiosity.

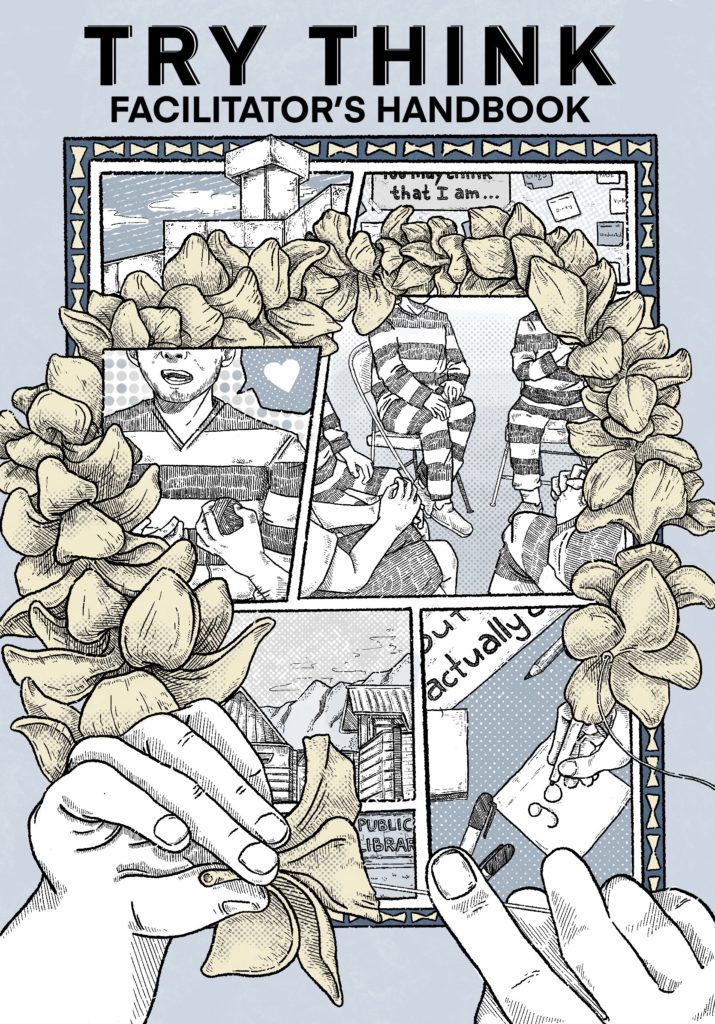

For my biggest challenge of the summer, the boss battle if you will, I took on what felt like a goliath of stories, experiences, and wisdom, and attempted to puzzle it all into the nine-page Try Think: Facilitator’s Handbook, which is a culmination of years of working to foster conversation and community in classes both in and beyond the prison system in Hawaiʻi. To receive such a wealth and weight of knowledge and to then transform into a visually appealing handbook—I mean—who was I to be trusted with such a task? All self doubt aside, the final piece is one I hope reflects the voices of the many individuals who contributed to the narrative of this project, the Try Think participants near and far, as well as a little bit of myself, my inspirations and passions. For example, the cover art is my experiment in how a manga artist in the public humanities might approach capturing community and facilitated conversation within spaces of incarceration. After days of agonizing over how to illustrate these themes in symbols and abstractions, I took the leap and drew a box—the building block of the comic—and started conversing with the piece in my native language.

Just to be clear, I’m not sure I’m a graphic designer, but among the many things I’ve learned this summer with HIHumanities, I know to not allow myself to be limited by barriers, whether it be the distinction between the nomenclature of artistic disciplines or the airwaves that both separate and connect us to those we love. On days when I would drain the entire lifespan of my iPad sketching abstract renditions of an illustration about x, y, and z, I had to remind myself that my contributions to the success of these projects and the larger field of public humanities lie in my ability to tell the story in the best way I know how. I am here to have faith and to put energy into the things I love and that bring me joy because they will sustain me and lead me through difficult times. It is for this reason that my summer portfolio reads like pages torn from the graphic novel that is humanities work in Hawaiʻi. It is the result of many nights spent drawing between breaks spent reading manga to the musical interludes of All Time Low and A Day to Remember. It is done in the hope that when scrolling the walls of a Facebook feed someone will see a drawing that allows their imagination to put four panels together to form a short narrative reminding them that stories and voices and art and love are strong enough to escape the black hole that is 2020. It is done from a place of aloha, aloha for myself, for my art, for those who converse with it; it is from my wahi pana, where I am alone in my head, but never in my heart.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rae Kuruhara is a retired barista turned grad student from Hilo who is currently learning how to skateboard. When not playing Animal Crossing or making gyoza, Rae studies public humanities at Brown University, where their research deals with Indigenous representation in popular culture, specifically comics, manga, anime, and video games.

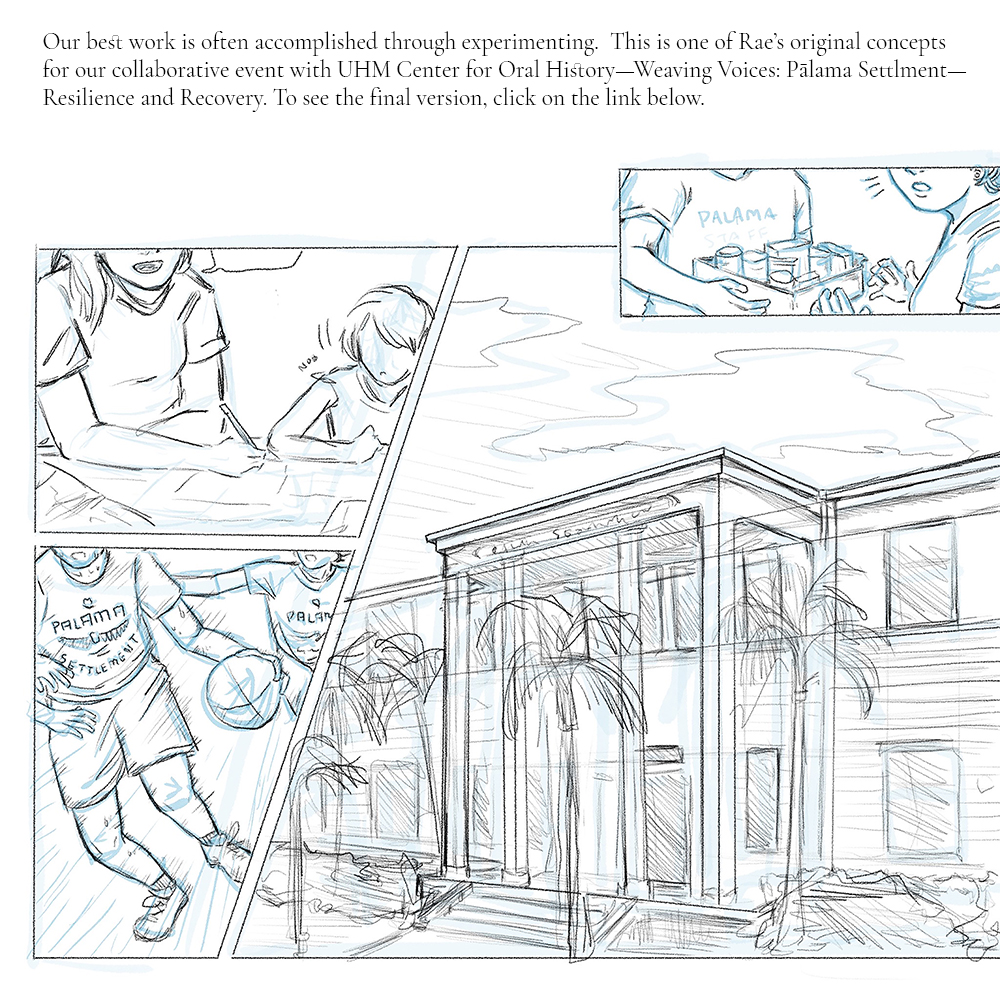

Weaving Voices: Pālama Settlement—Resilience and Recovery

Nā Mana Wai aims to highlight a diversity of community voices from around our islands and is intended to raise important questions that will lead to continued productive discussion. The opinions expressed here do not represent those of Hawaiʻi Council for the Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.